REVIEW

SEPTEMBER 17, 2023 – JANUARY 20, 2024

EMILIO AMBASZ INSTITUTE FOR THE JOINT STUDY OF THE BUILT AND NATURAL ENVIRONMENT

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK

ORGANIZED BY CARSON CHAN

I visited Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism at MoMA three times. The first time was with friend and colleague Helen Runting of Stockholm-based architecture practice Secretary; the second was with fourteen fourth– and fifth–year architecture students from New Jersey Institute of Technologies’ (NJIT) Architecture Program; and the third was on my own, to try, one last time, to make sense of a complex and multilayered exhibition.

Organized by Carson Chan, Emerging Ecologies explores the architectural response to the United States’ environmental crisis in the 1960s and 1970s. The installation includes work from Emilio Ambasz. His recent $10 million gift founded the Ambasz Institute for the Joint Study of the Built and Natural Environment, the research institute at MoMA responsible for the show. Ambasz’s work is prominently featured including models of the Casa de Retiro Espiritual in Spain (designed 1976–79, built in 2000), Prefectural International Hall in Japan (1990), Lucile Halsell Conservatory in Texas (1982), and Eni S.p.A. Headquarters in Italy (1998).

Figure 1. Photographs and models of Emilio Amabasz’s buildings.

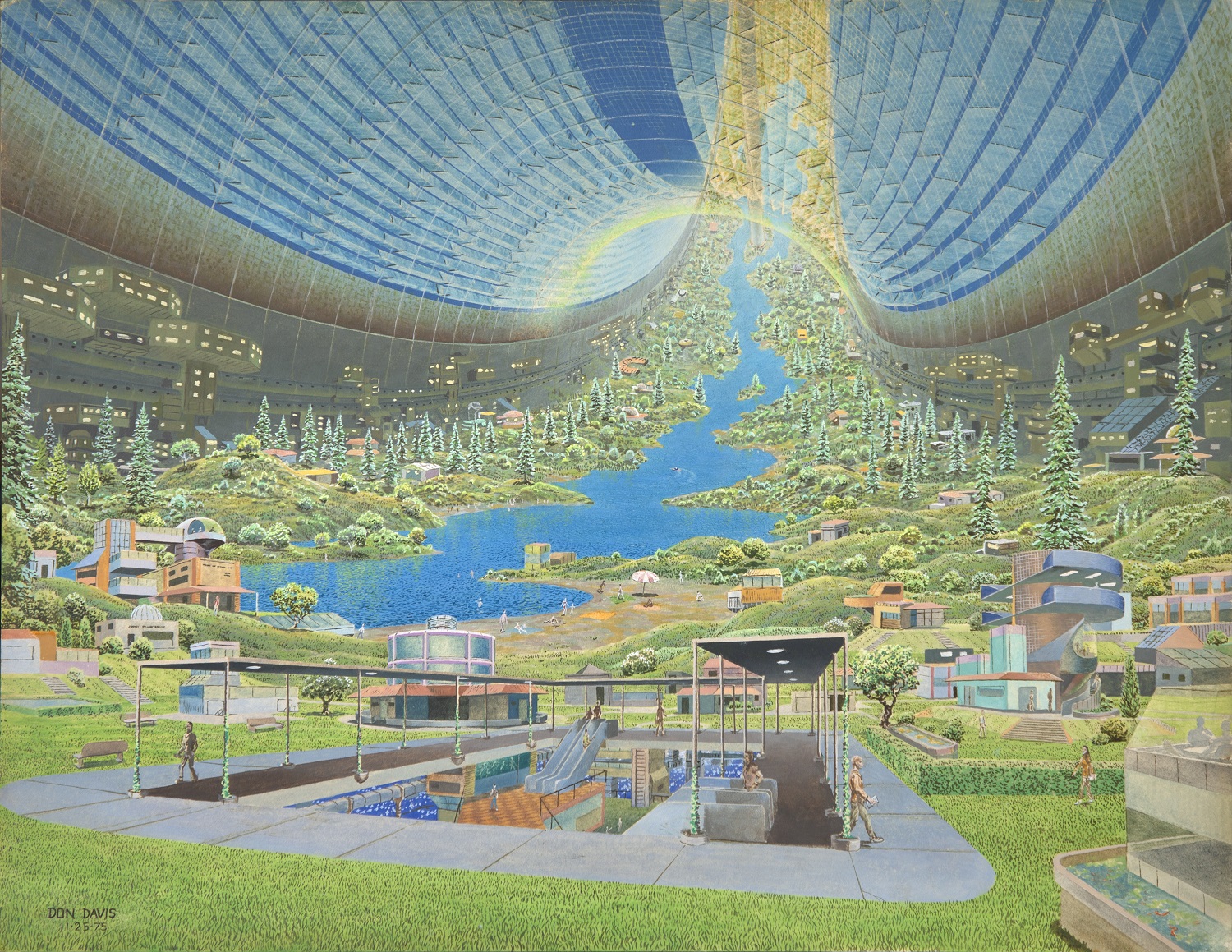

Other featured projects are fantastical: notoriously self-mythologizing Buckminster Fuller’s 1960 proposal for a geodesic Dome over Manhattan; James Wines’ 1981 poetic amalgam of urban and suburban in Highrise of Homes; and Gaetano Pesce’s mid-1970s Church of Solitude Project, an escape from corporate culture. Others are shockingly timeless. For instance, the video and model for Eames Office’s proposal for the National Fisheries Center and Aquarium are as effective today as in 1967. Commissioned by NASA, Rick Guidice’s and Don Davis’ impressive 1975 gouache and acrylic paintings are some of the smallest (and most detailed) works in the exhibition. The NJIT students immediately saw them as the inspiration behind the 2014 film Interstellar.

Figure 2. Don Davis, Stanford Torus Interior View, 1975, acrylic on board, commissioned by NASA. Collection Don Davis.

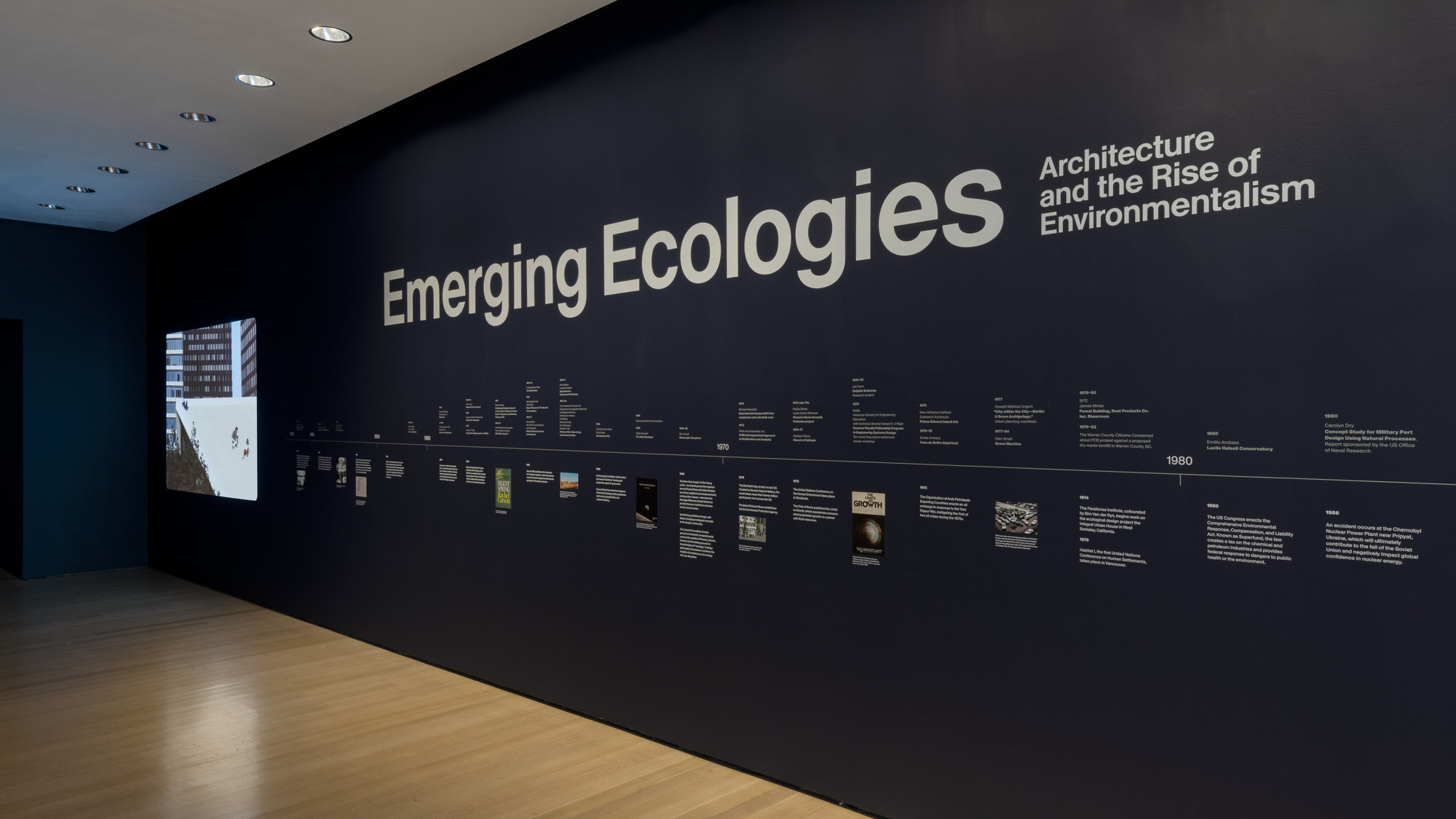

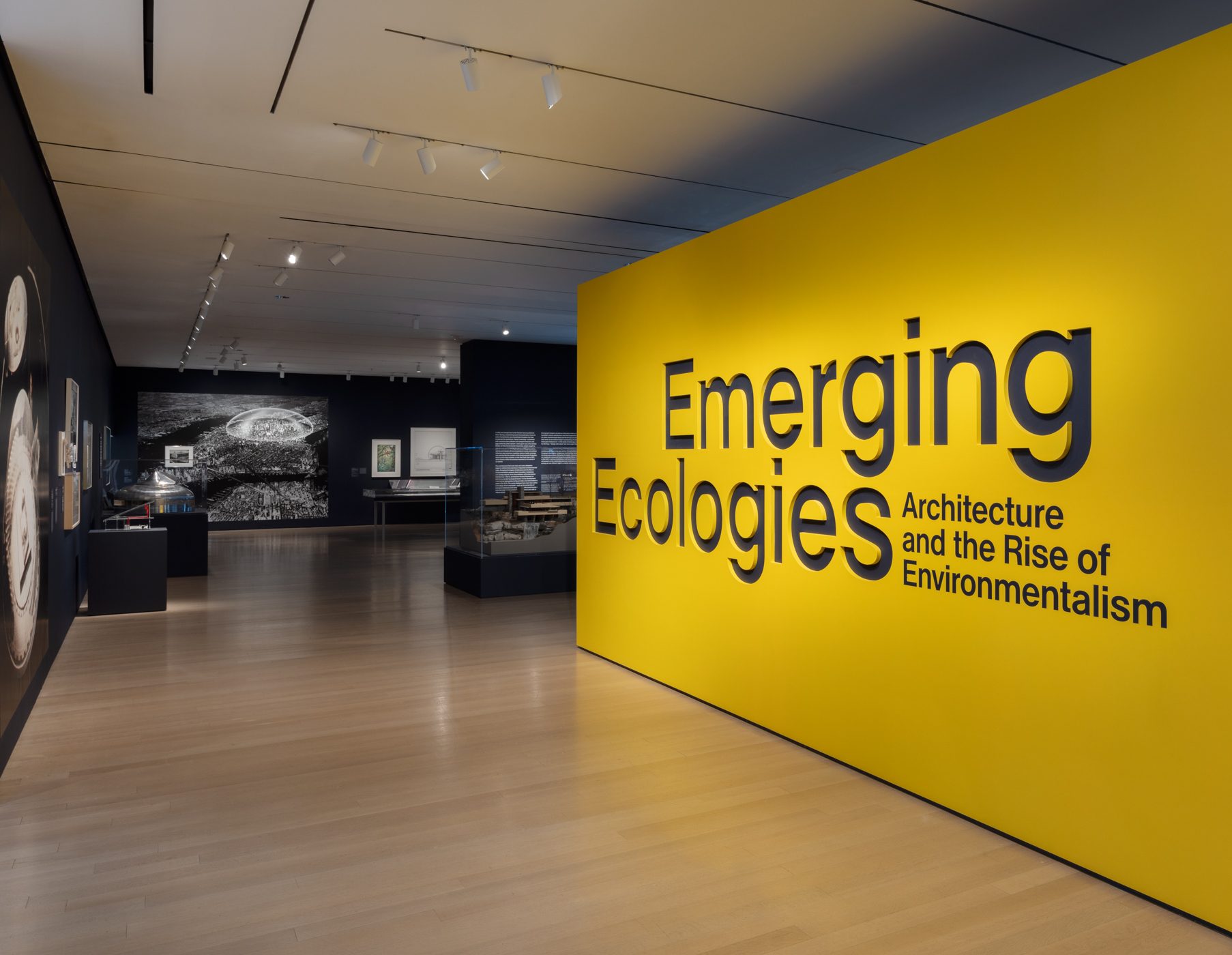

The exhibition’s atmosphere feels futuristic, enveloped by nearly black walls, intense spotlights, and projections throughout dark rooms. Two massive bright yellow title walls sit in graphic contrast to the darkness and block nearly all daylight from MoMA’s atrium on one side and garden court on the other. Just beyond the entry wall, a large model of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater sits in front of a projection of a Buckminster Fuller Dymaxion map, setting up a photogenic tableau. An impressive timeline, developed in part by students and faculty at the University of Virginia, positions the exhibition pieces in relation to social and political events. It could have served as a roadmap for the exhibition if located near the entry, but instead it feels like an afterthought strangely positioned in an elevator lobby.

Figure 3. 1984 model of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater (1937) backgrounded by Buckminster Fuller’s World Game (1970).

Figure 4. A view of the exhibition’s timeline showing each piece in the exhibition along with critical contemporaneous social, political, and cultural events.

On my first visit with Helen Runting, a tall gentleman stood in front of work by Glen Howard Small. He was clad mostly in black, wearing a cowboy hat and architect’s glasses—an unlikely combination. A quick Google search returned an obituary for Small, so I was surprised when he introduced himself as the architect behind the works on display. A long conversation with Small tore down the museum’s metaphorical wall and brought the exhibition to life, enriching it with stories of the personal dramas of Sci-Arc in its formative years and the human, emotional drive behind the creation of these works envisioning a fantastical future. The show includes Green Machine, his late 1970s concept model for multifamily housing created by stacking airstream trailers onto a multitiered steel platform; a circular wall-hung relief model and three intricate colored pencil drawings of Biomorphic Biosphere, a society within an organic tubular enclosure set upon a barren landscape; and a 1978 television interview with a much younger man. It turns out Small wrote his own obituary as a kind of public statement, to reflect on his life and work: “his projects used the technology of our era,” he wrote, “and projected what could be, if the society chose to implement them.”

Figure 5. Helen Runting and Glen Howard Small in conversation with his piece Green Machine (1980). Photo: Carrie Bobo.

Figure 6. Glenn Howard Small’s Green Machine with University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Landscape Architecture Upper Delaware Estuary Maps in the background.

Figure 7. Glen Small (American, born 1937). Biomorphic Biosphere Project, 1969–82. Drawing of a flying house. 1973. Ink and watercolor on paper, 16 × 20″ (40.6 × 50.8 cm). Collection Glen Small.

The NJIT students homed in on this idea during our visit: we as a society have the capacity to end, and even reverse, climate change if only we were interested in making that choice. The students are a diverse group of largely first– or second–generation Americans from Colombia, Egypt, Mexico, North Korea, Pakistan, Puerto Rico, India, and Peru. They were quick to point out that the exhibition imagined a future that didn’t include people who looked like them—perhaps a critique of the era more than the show. While the curatorial team clearly worked to include diversity in the exhibition, these pieces sit at the periphery, background to the work of the canon; the familiar works of Wright and Fuller are placed front and center.

Many pieces by diverse voices could have easily been foregrounded. Of unique pedagogical value are the sketches women cocreated as part of Phyllis Birkby’s 1975 Women’s Environmental Fantasies project. Their process sketches inspired the NJIT students; the museum context imbued often-disposable work products with value. The students also connected with the 1980 work of Carolyn Dry exploring ocean platforms grown from coral. Commissioned and published by the US Office of Naval Research, Dry’s drawings integrate natural processes with technology, showing powerful opportunities for the construction industry. This theme continued with architect Beverly Willis’s groundbreaking development of CARLA (Computerized Approach to Residential Land Analysis), an early use of computers to protect natural environments. Willis developed CARLA in response to Ronald Reagan’s California Environmental Quality Act of 1970, which required environmental impact reports. Willis’s work could have been a keystone for the exhibition, linking technology to ecological protection, but instead ideas are presented on letter-sized printouts literally blown out by glare from Fuller’s massive World Game.

Figure 8. Installation view of images from Beverly Willis’s CARLA Drainage Map, Site Geology & Soils, Cut & Fill Analysis, Site Geology & Soils of Crestview Hayward Townhouses, Hayward, California 1971. Inkjet reproduction (matte) 8 1/2 x 11″ (21.6 x 27.9 cm) ,Virginia Tech University Libraries. International Archive of Women in Architecture. Beverly Willis Architectural Collection.

Carolyn Dry is also included in the exhibition’s overlay of recordings titled Meditations in an Emergency, featuring female architects (with one obvious exception, Emilio Ambasz); Amy Chester, Carolyn Dry, Meredith Gaglio, Jeanne Gang, Mae-ling Lokko, and Charlotte Malterre-Barthes. These powerful recordings slow down the experience of the exhibit, guiding the visitor to reflect—that is, if you notice them. Much like the timeline, I nearly missed them on my first visit. They are worth paying attention to.

Figure 9. A family listening to one of the Meditations in an Emergency positioned between James Wines’ Highrise of Homes to the left and Gaetano Pesce’s Church of Solitude Project on the right. Photo: Carrie Bobo.

After seeing the exhibition, the students and I sat for a while in Paley Park. The students suggested that the architects included in the exhibition would likely be disappointed by the future; 60 years later we’re all still playing around with the same problems. The students found the words of many of the audio recordings resonant, particularly those of Malterre-Barthes:

I would like to see a non-extractive architecture emerge. To propose an architecture that is aware of its harm generating practice. And that addresses that. So, decarbonize, depatriarchalize, decolonize the discipline at all levels.

These themes of avoiding harm are still with us. The curators tie the ecological movement in architecture to environmental protest. The show includes images of a protest against the construction of a landfill for PCB-contaminated soil in a majority Black area of North Carolina as well as the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation’s opposition to the Orme Dam in Arizona. The project, approved in 1968, would have flooded two-thirds of the Nation’s lands had it not been stopped by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. Ironically, just days before the exhibition opened, MoMA closed its doors for five hours because of a protest against the institution’s ties to investments in fossil fuels, in particular its deep financial relationship to the private equity firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts. The protestors demanded that the museum’s director meet with Wet’suwet’en First Nation leaders, whose territory is threatened by the construction of the Coastal GasLink Pipeline, a project partially funded by KKR. Sixteen protestors were arrested.

Figure 10. Protesters marching against a PCB landfill in Afton, Warren County, North Carolina. Installation view of Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, on view at The Museum of Modern Art from September 17, 2023 through January 20, 2024. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

Yet it’s not enough. On my third visit to the show, alone, I realized: Emerging Ecologies is a red flag. These projects show us architectural visions from the past in direct poetic dialogue with the promise of a more diverse future. And yet we’ve failed to realize that future. Unfortunately, we don’t have time left. We sit at the precipice of climate destruction on a foundation of racialized Modernism. I am reminded of MoMA’s groundbreaking exhibition from 61 years ago, Architecture without Architects. In a memorable review, Ada Louise Huxtable wrote:

More than an exhibition, then, this is a protest—a pointed, bitter, desperate broadside from a cultivated, rebellious heart and mind against the sacrifice of the well‐built landscape to the urgencies of the industrial, nuclear age.1

The show’s wall text describes this as the first in a series, so perhaps the next exhibition will, borrowing the words of Malterre-Barthes and Huxtable, showcase harm and extraction to advocate for decarbonization, depatriarchalization and decolonization; an exhibition not of nostalgia, but of open protest.

Carrie Bobo, RA, professor of practice, New Jersey Institute of Technology is an artist, educator, and registered architect with more than 15 years of professional experience, most recently at an ambitious young firm in Göteborg, Sweden focused on affecting the structure of the city, Sunnerö Architects. Previously, she was associate with Selldorf Architects where she designed and managed arts exhibition, residential, and institutional projects. Bobo teaches on climate responsive building forms and indigeneity as a resource for the design of sustainable housing with New Jersey Institute of Technology where she founded and runs the Scandinavia program. Bobo is committed to thoughtful urbanism, equity, and holistic sustainability.

Many thanks to the students of New Jersey Institute of Technology: Alexana Araujo, Evan Carroll, Lodie Elmarry, Gerardo Flores-Alejo, Carlos Gallardo, Joseph Halbert, Griffith Humphrey, Abdulahad Malik, Loc Nguyen, Roberto Osorio, Dereck Pablos, Megha Patel, Salvador Suaza, and Albina Zhaku for sharing their valuable insight and reflections.

Notes

- Ada Louise Huxtable, “Architectless Architecture: Sermons In Stone,” New York Times, November 15, 1964, sec X., p.23, for copyeditor can we make this an inline link edit? https://www.nytimes.com/1964/11/15/archives/architectless-architecture-sermons-in-stone.html.

Figure Citations

Except as noted: Installation view of Emerging Ecologies: Architecture and the Rise of Environmentalism, on view at The Museum of Modern Art from September 17, 2023 through January 20, 2024. Photo: Jonathan Dorado.

How to Cite This: Bobo, Carrie. Review of Emerging Ecologies, JAE Online, [date here]