The word “H2O” sits uncomfortably on our tongues. While the word “water” harbors a host of divergent social, cultural, and theoretical meanings, the scientism underlying H2O distills the idea of water to its molecular structure, devoid of pluralistic, overlapping, or competing worldviews. In so doing, H2O denies or obfuscates the diversity of values and vested interests that water can hold. How might we better understand the complex stories surrounding water that might, in turn, help us create a more optimistic future?

We began thinking about this issue with a curiosity about what water could become in the future. Joining us, authors brought their own experiences to bear on understanding water and looked for ways to explore the many values engaging water. In this issue of JAE, we can appreciate the enormity of the scales and various nuances through which water and design mix: demonstrated by the broad range of types of projects and of embedded attitudes. Architecture, planning, and landscape architecture projects all engaged with the challenge of water, even while we note that the distinctions between these disciplinary boundaries have become increasingly irrelevant today. Indeed, the topic of water makes this profoundly clear because water, like the air we breathe and share, is a connecting force.

Hadley Arnold begins with an abecedarium to develop a capacity to talk about the future, while Kate Orff grimly illustrates the current state of affairs, urgently calling for a visionary, large-scale “Teal New Deal.” Two sets of discursive images also ground this discussion. Anuradha Mathur and Dilip da Cunha remind us that the line between land and water is an artifice, suggesting that while a separated water is in crisis, “wetness negotiated everywhere holds the way forward.” On a more pragmatic level, Antje Stokman and Dagmar Pelger call attention to the topic of a third space for water with the story of their critical public engagement initiative for Hamburg’s Bille River.

In three different interviews, we invited leading practitioners to give voice to their experience of working with water. Peter Olshavsky interviewed Steven Holl, highlighting the experiential and poetic qualities of water. Meanwhile, Alpa Nawre interviewed both Herbert Dreiseitl and Elizabeth Mossop to bring lessons from landscape practice and leadership into focus. Dreiseitl sees water as an inroad into a more intentional social practice, while Mossop recognizes the practices and scholarship that could affect change in this realm. All three of these practitioners have spent decades working with water through their design practices, and their insightful experiences provide models for sustained engagement.

Three Scholarship of Design pieces help to draw out the role that values about water play in the shaping of spaces. Danika Cooper picks apart water’s ontological and linguistic barriers and highlights their entrenched power in her piece on Arizona’s Orme Dam, making a case for using action to subvert dominant paradigms. In the same geographical area, Danielle Narae Choi uses infrastructural histories to help our understanding of the postnatural world and cultural desires. And in Guyana, Gabriel Arboleda invokes the term “bottom-up social design” to reassert client values in his project involving self-help housing, roofing choices, and rainwater catchment.

The Design as Scholarship submissions highlight the power of design thinking to imagine alternative futures. Jonathan A. Scelsa and Jennifer Birkeland propose a water-energy infrastructure plan for Tokyo that they call “The Next Urban H2 Order,” María Arquero de Alarcón employs “environmental storytelling techniques” with students to conceptualize Indian water potentials, and in “A Flooded Thirsty World,” Rania Ghosn uses speculative fiction to highlight the climate crisis. H2O is also charted as a border condition: Derek Hoeferlin outlines a system for addressing the challenges of transboundary water space in China, just as Kathy Velikov and Geoffrey Thün look to shared water resources along the US-Mexican border. Finally, two examples of community-based design engagement are highlighted: Ann Yoachim, Emilie Taylor Welty, and Nick Jenisch describe selected projects in New Orleans, and Miho Mazereeuw, Aditya Barve, and Lizzie Yarina describe a single water hub action-research project in Nepal.

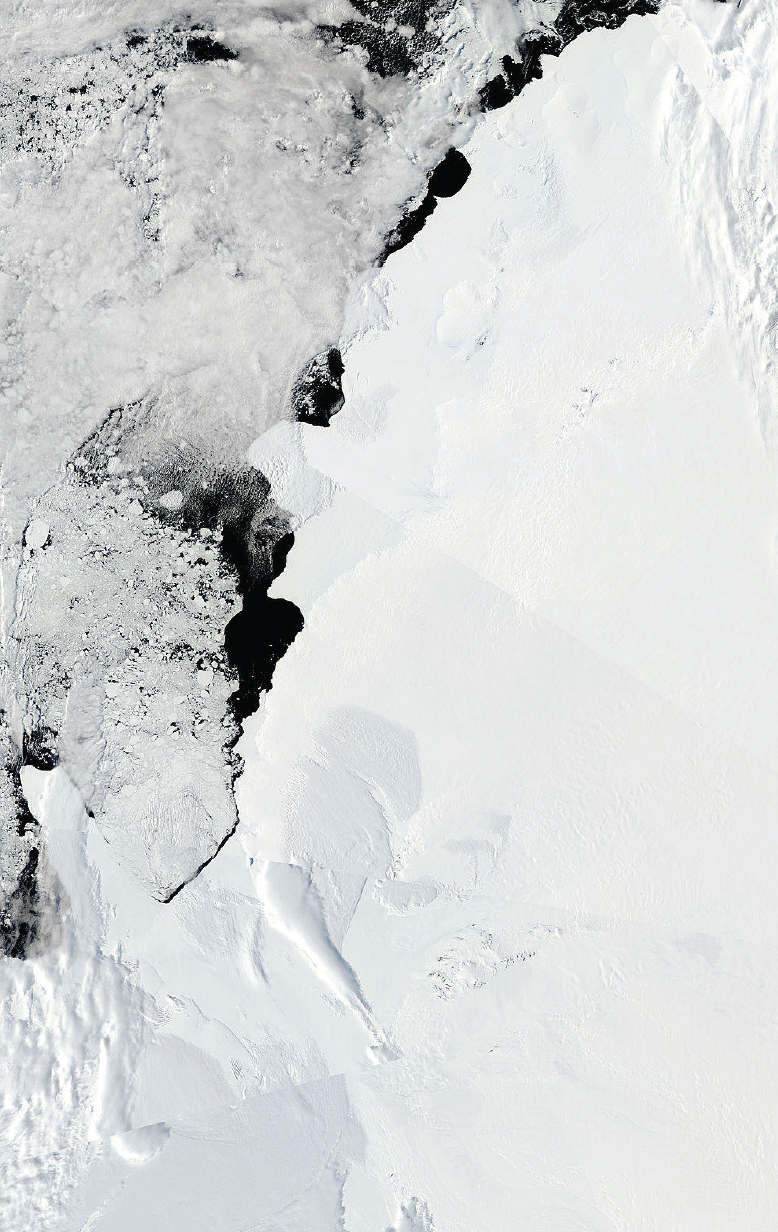

Similarly, several “Micro-Narratives” provide encouraging evidence of how design professionals might reconsider the roles of water. Kees Lokman and Karen Tomkins look at alternate worldviews from indigenous communities of the Pacific Northwest for lessons on human-nonhuman relationships, calling for collaborations to bridge distances between indigenous and scientific communities. Leena Cho articulates the biases of the hydrological cycle and invites designers to take cues from the transformation of frozenness in the Arctic. Eliyahu Keller and Kelly Leilani Main provocatively question the enterprise of concealment that architects are complicit in when developing design “solutions” for climate change challenges, calling for an architectural imagination that can help to reveal what is hidden. In India, Priya Jain uncovers layers of cultural nuances through documentation of the exhaustive maintenance needed for a colonial relic facing the perpetual wetness of the Asian monsoons. Finally, Emily Vogler and Jesse Vogler shed light on the irrigation ditches, the acequias, of the Middle Rio Grande Valley and call for an “informed ditch public” and future commons to be built upon this system.

In the context of the Anthropocene, what we do now matters more than ever before. Acute environmental conditions, such as water scarcity and flooding, are necessarily reframing attitudes toward water in communities around the globe. As designers, we find ourselves suspended in a moment of water crises—we must prepare and question actively, at all scales and in all contexts. In the built environment, the mechanics of working water systems remain largely invisible. Water runs beneath the surface, both physically and metaphorically. Water moves through regions, cities, and buildings, mostly contained, often overlooked, and infrequently acknowledged. Even dangers posed by rising sea levels, by mudslides, and by inundation only rarely find legibility. This invisibility and the implicit design concurrence with business as usual provide the most compelling reasons to interrogate the values that make the world around us.

Water connects people and places across the Earth’s surface. But it is the meaning held across cultures, time, and space that makes for an even more compelling case of connection. Water is a mighty, value-laden signifier. Could such framing, and associated design thinking, actually craft changes in contemporary social, cultural, religious, environmental, and economic values? Might there be an opportunity to shift public awareness and make strides toward more equitable development? As amply evidenced by the submissions for this issue of JAE, this attitude calls for designers to be more: to become agent provocateurs, activists, facilitators, and initiators. It calls for individuals to transcend the street-fights, state-fights, and nation-fights in which water operates as a divisive instrument. We invite our collaborators and our readers to build upon these conversations through action and public discourse. Throughout time and space, water has brought people together in both physical and conceptual ways. And water can continue to connect us, by serving as a powerful framing device to embolden practice and by becoming the basis of our combined efforts toward a better future.

ACSA members can access the full issue here.

Continue Reading: