Robin Schuldenfrei

Routledge, 2020

It appears as though we are in the midst of a florescence of scholarship on design process. This is perhaps the most logical of next steps for a field that is at once attempting to break free of the circumscription that nationalist geographies impose as well as the hagiographic constructions of authorship that limit exactly who has agency in design. After all, all architecture, like materiality, involves process and this universality may act as something of a unifier in trying to make sense of the postnational and post-hagiographic landscape. Appropriately, much of the best scholarship in this arena is emerging out of edited volumes where multiple authors (and editors) are able to come together to meditate in multimodal fashion; Terms of Appropriation: Modern Architecture and Global Exchange (Amanda Reeser Lawrence and Ana Milijački eds., 2017) and Design Technics: Archaeologies of Architectural Practice (Zeynep Çelik Alexander and John May eds., 2019) are just two recent examples. Is this florescence a “turn to labor,” as the sociologist Andrew Ross has phrased it?1 Is it a revival of the process-centered approach modeled by Siegfried Giedion in his Mechanization Takes Command?

The newest edited volume to center process, Iteration: Episodes in the Mediation of Art and Architecture, edited by Robin Schuldenfrei, offers us some clues into this trend. Iteration’s objectives are refreshingly uncomplicated; according to a blurb on the publisher’s website, the book considers “the ways in which multiple stages, phases, or periods in an artistic or design process have served to arrive at the final artifact, with a focus on the meaning and use of the iteration.” So as to frame the iteration within artistic and architectural production multivalently, the essays in this volume comprise focused “episodes” in art, architecture, and design history, deploying archival research and historiographical analysis as well as media and critical theory. Unifying the volume’s eight chapters and coda, Schuldenfrei argues, is the throughline that objects (be they buildings or works of architecture) ought to be seen not “as unique and immutable works” (vi-vii), but rather through an examination of their antecedents, successive exemplars, their afterlives, and their role as repositories of meaning.

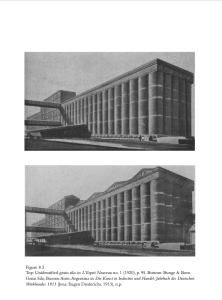

In reading the essays, one is presented with an episodic assembly of arguments. For example, there is the rather varied way in which iteration—as a concept—is individuated among the essays. In Schuldenfrei’s own essay, entitled “Iteration of the Non-iterative: Revaluation and the Case of László Moholy-Nagy’s Photograms,” as well as in Kathleen James-Chakraborty’s contribution entitled “Sonia Delaunay: Media or Message?,” iteration is framed as a solitary artistic process. It is a step in a formal, visual experiment that not only uses but relies on multiple media for its realization: photograms and enamel paint for Moholy-Nagy, textiles and industrial design for Delaunay. In both cases, we have the extraordinary parallel of an intimate interlocutor who happens to be an influential spouse (Sibyl Moholy-Nagy to László Moholy-Nagy and Robert Delaunay to Sonia Delaunay), who may or may not factor into the nature of artist’s iterative practice. (Note that this ambiguity calls into question the iterative-ness of historiography.) In Peter Sealy’s essay “The Image as Iteration,” there is no such solitary individual. We are, instead, introduced to the individuated decisions of architects and architectural historians who re-iterate (and willfully misrepresent) the works of photographers to unify a point. Sealy addresses the particularly slippery phenomenon of architects who edit out mechanical equipment or other unsavory visual information from their press photographs (in the storied tradition of Le Corbusier). Zeynep Çelik Alexander’s essay “Managing Iteration: The Modularity of the Kew Herbarium” disperses iterative agency onto the user of the herbarium at the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew in London. Çelik Alexander’s convincing argument suggests that it is neither the architect nor the work of architecture itself that acts iteratively. Instead, a building, much like an Excel spreadsheet, is merely the framework for the data entry and interpretation of an anonymous class of botanists and colonial administrators who manifest infinitely renewable iterations of colonial and botanical power-knowledge within the building-database.

Figure 1. Top: Unidentifed grain silo in L’Esprit Nouveau no. 1 (1920), p. 95. Bottom: Bunge & Born Grain Silo, Buenos Aires, Argentina in Die Kunst in Industrie und Handel: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Werkbundes 1913 (Jena: Eugen Diederichs, 1913), n.p. Credit: Iteration, p. 161.

Figure 2. The National Herbarium of New South Wales, Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney, circa 1895. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

These differences produce a productive tension in the book, one that offers the reader different ways to conceptualize iteration as artistic and monophonic (a single author iterating) or polyphonic and social (multiple people forming an iteration). The reality is cacophonic and this might disappoint those looking to emerge from this volume with a unified idea of iteration. Perhaps some of the tension comes from the fact that so many different media practices (photography, industrial design, textile design, architecture, photography, graphic design, painting) are placed cheek by jowl in such a relatively short collection. Surely iteration has very different guises in the authorial contexts that make buildings than it does in those that make paintings.

In the essays of Schuldenfrei, Sealy, and James-Chakraborty, the ability to iterate is articulated as an expressly individual activity, be it in the originary process of the artist or in the retrospective process of the historian. Even as we are aware of the intimate human forces acting on those iterations—be it a spouse or a photographer or the architect of a building in a photograph—it is from the individual alone that an iteration of something can emerge. Çelik Alexander’s essay goes against that authorial grain. Instead, she conceives as a kind of chorus, multivalent and indivisible.

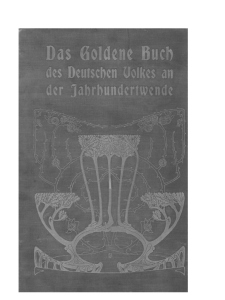

This question of who has the authority to issue an iteration serves to remind the reader of the very meaning of the word iteration, which refers to speech—to iterate. No two voices will ever sound the same, no matter if they try to synchronize. In other words, the opposite of the singular authorial nature of the others. Other essays include Michael Gnehm’s “A Spiraling History of Architecture,” Peter H. Fox’s “Bernhard Pankok’s Graphic Iterations,” Molly Warnock’s “Simon Hataï after Pliage,” Mike Ricketts’ “In and Out of View: Reflections on The Vessel,” and Timothy Hyde’s coda “The Interchronic Pause and the Temporality of Iteration.” The variegation of that thematic thread present in these essays is precisely what makes the book a productive compendium on the related theme of authorship. The book provides several well written and transmutable models for locating the distinction between authorship in art, authorship in architecture, and authorship in design. In one case, iteration may function as an equivalent to the fingerprint, an imprimatur of a solitary mind and hand. In another, it functions, as Roland Barthes suggested in Death of the Author, as the diffuse manifestation of many.

As we recall the “turn to labor” that seems to be behind this book, we could go one step further than this volume by interrogating iteration’s emancipatory potential, both for design thinking and historiography. If we are to advocate for the importance of art, architecture, and design, what way of framing iteration, from those on offer here, is most emancipatory? Shall we place that practice squarely in the hands of the individual or in the collective? Does either presuppose a destination and does this destination reveal what we want art, architecture, and design to do?

Figure 3. Bernhard Pankok, cover of Das goldene Buch des Deutschen Volkes an der Jahrhundertwende, ed. Julius Lohmeyer (Leipzig: J.J.WeberVerlag, 1899). Credit: Iteration, p. 56.

Notes:

See Andrew Ross, “Foreword,” in Peggy Deamer, Architecture and Labor (London: Routledge, 2020), viii.