Julia Watson

Taschen, 2019

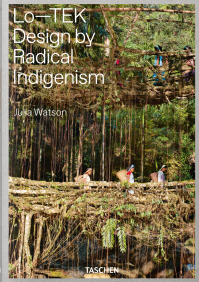

Dedicated to the next seven generations, Lo-TEK. Design by Radical Indigenism challenges contemporary measures of performance, productivity, and efficiency. Author Julia Watson draws upon Indigenous philosophies and long developed intergenerational knowledges for managing environments and building cultural practice. In this, her book resonates with the expanding publications of Indigenous authors who offer object lessons of autochthonic culture and wisdom in relation to place. Watson does not claim to be of Indigenous heritage, and in this light, we can only assume she has sought permission to relay the information provided in her essays. It is important to articulate that she does not seek to co-opt Indigenous methods and strategies, but rather contemplates and considers their approaches to suggest opportunities, both large and small, in our efforts to generate sustainable and climate-resilient infrastructures.

Watson offers Lo-TEK, a conceptual synthesis of Lo-Tech (low technology) and TEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge), as a movement built from the Indigenous knowledges she has had the privilege to be introduced to in her extensive world travels. Inspired by architect Bernard Rudofsky’s 1964 MoMA exhibition, titled Architecture Without Architects, she describes Lo-TEK as a vernacular path for design that reimagines the professionalization and Eurocentric pedagogies of contemporary allied design and planning fields. Her fundamental premise is to develop new interpretations and mythologies for Western cultures that will deepen peoples’ relationship to their environment. She centers and elevates knowledges generated in the experiences of quotidian successes and failures, refined over generations. While these connections often reverberate in the undertones of global development dialogues, they have been mostly lost in the chorus of colonial advancement and manifest destinies dominating the past four centuries.

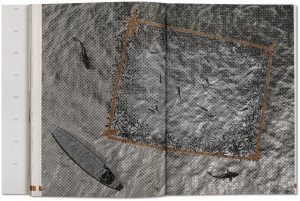

Figure 2. The acadja fish paddocks constructed and maintained by the Tofinu people of Benin are a low-cost, sustainable aquaculture infrastructure supporting small-scale, but high-yield returns while maintaining local biodiversity.

In common with other Taschen publications, the material design of the book is beautiful with every detail well-constructed—from a detached binding to a creative layout to the liberal use of spatial mappings, technical diagrams, evocative representations, and colorful images. Each case, and for that matter, each page, is thoughtfully designed, offering the opportunity to learn from Indigenous ways of living and being in this world. One might open the book at random, to be immersed in cultural practices grounded in intergenerational knowledge and paced with the rhythms of place.

While the bounding chapters offer focus and definition for a new mythological perspective that accepts knowledge as multiplicitous, temporally framed, and socially constructed, the introduction and conclusion offer merely a thin veneer, bounding the richness described in Watson’s compendium of case examples. Comprised of eighteen case studies, organized into four sections (“Mountains,” “Forests,” “Deserts,” and “Wetlands”), and five interviews, the book’s core is a lush and immersive read. While each case is independent, and geographically and culturally distinct, they are intrinsically linked through water—whether omnipresent, in deluge, or in scarcity.

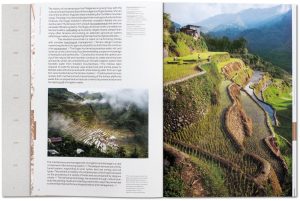

In “Mountains,” the case studies are innovations from mountainous regions of the world where Indigenous people, communities, and cultures have thrived for millennia drawing upon the land and the life it supports to physically and spiritually shape their worldviews. For example, the rice terraces, known as palayan in Filipino, represent an innovative terraforming technology of the Ifugao people on the steep mountainous isles in the Philippines. The centuries-old terrace technology forms a cascading system of carefully tended agricultural plots enabling the growth of a diverse ensemble of rice species, a staple of the Ifugao diet. Ifugao creation stories are deeply entwined with the rice species, and impart the importance of diversity as integral to sustaining livelihoods.

Figure 3. The Ifugao’s terracing practices serve as an innovative model of terraforming that irrigates, purifies, and provides a platform for community-driven ecological rice farming.

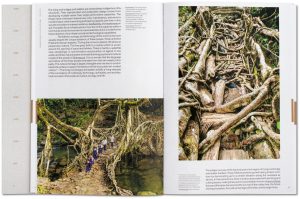

The Khasi tribe of what is contemporarily known as northern India live in a steep region of lush forests with one of the highest levels of annual precipitation found on earth. During the monsoon season, the interspersed communities of the Khasi are cut off from one another as the water “transform[s] the landscape from a thick canopy to isolated forest islands” (47). To adapt, generations of Khasi people have shaped and tended the roots of the endemic rubber tree fig into resilient, living bridges connecting their communities. As Khasi architect Prabhat Dey Sawyan describes, “The knowledge and skills of construction of the living root bridges is passed down from one generation to another, purely through its usage in the communities” (71). They provide a direct connection for intergenerational learning, and a broader lesson for developing and maintaining innovative, living technologies that respond to ever-changing conditions.

Figure 4. Ingeniously woven and grown from the local rubber fig tree, these living bridges are a critical infrastructure connecting the dispersed communities of the Khasi people during the monsoon season.

In “Forests,” Watson provides examples of resonating Indigenous knowledges in sustaining strong interrelations with the communities of species, plants, animals, and others that comprise their environment. Deep in the Amazon rainforest, the Kayapó people seasonally burn small circular areas of highly tended and actively managed locations transformed into agricultural villages, regionally known as apete. Through practices of semi-domestication, they have partnered with a variety of stingless bee species that not only provides wax and honey, but also serves as pollinators for cultivated species of plants. The Kayapó believe that their ancestors modeled their social hierarchies from their interactions with these bees, establishing convivial relations decentering human priorities for the benefit of the inter-species community.

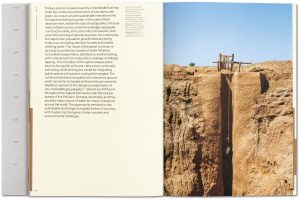

In “Deserts,” the scarcity of water and harshness of conditions have shaped the lives of many cultures. In the driest regions of east Africa, the Ngisonyoka Turkana people migrated to the region over the past several hundred years, establishing cultural practices of collection and dispersal, recognizing the need to draw on all that surrounds them to maintain their livelihoods. Their knowledge is born from their survival in these unforgiving conditions, developing methods of arid farming practices, and domesticating a wide variety of species including sheep, goats, cattle, and camels. Practicing a semi-nomadic lifestyle, they relocate seasonally in relation to water availability. They construct temporary corrals from locally harvested woody plants to contain their livestock, which also serve to hold moisture and fertilizer, in turn supporting the germination and growth of a next generation of plants to maintain the cycle.

At a moment when scholars, designers, and teachers are interrogating the potentials of other forms of knowledge, and in particular indigenous knowledge, Lo-TEK. Design by Radical Indigenism offers a narrative grounded in the complexity of our world’s cultures and environments. The essays Watson provides are just a small sampling of the multitudes of distinct Indigenous knowledges and spiritualities that have shaped and sustained cultures in some of the harshest environments on the planet. While all of the cultures featured in Watson’s book are under threat from external pressures including the capitalization of agriculture, anthropogenic climate change, and tourism, they open possibilities for a difference in thinking, asking, and learning. We cannot afford to lose these insights, yet indigenous knowledge is not to be merely assimilated, but must be learned and respected. Watson’s writing recognizes that while these cultures and the lessons they hold are not ours, we have the privilege to engage respectfully, and to learn from their practices, not as something historical, but as knowledges that are living, growing, and adapting in our contemporary world.

Ken P. Yocom is an environmentalist, author, educator, and strong proponent of community stewardship in environmental rehabilitation. His creative and professional pursuits engage an opportunities-based approach to support residents of underserved communities to build greater connections to place through urban ecological design projects. Trained as an urban ecologist and landscape architect, he is an associate professor and chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Washington-Seattle.

How to Cite This: Yocom, Ken P. Review of Lo-TEK. Design by Radical Indigenism, by Julia Watson, JAE Online, February 12, 2021.

All images used in this review are promotional mock-ups courtesy of Taschen.