New Jersey as Non-site at the Princeton University Art Museum brings to light the important and to date unacknowledged role that New Jersey had in shaping poststudio art between 1950 and 1975. Curator Kelly Baum, Haskell Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, frames New Jersey, not as second to New York or a drive through state en route to Philadelphia or Washington DC, but rather as a real

garden state, fertile ground for much of the era’s most significant works: from Robert Smithson’s nonsites (

A Nonsite [Franklin, New Jersey], 1968) and Allan Kaprow’s Happenings (

Calling, 1965) to Gordon Matta-Clark’s popular

Splitting (1974).

Poststudio practice carries with it a kind of nostalgia, at least when framed alone as a move away from studios and galleries toward everyday life, the street, and eventually toward vast, unobstructed landscapes in the American Southwest. Baum offers a more complex view, selecting some 100 objects that maintain a connection between New Jersey and the cultural, social, and political worlds at large. Leo Marx, who in 1964 argued that more was at work in American literature than nostalgic pastoralism, focused on the importance of particularly connective moments (say, the incursion of a train into a peaceful countryside).

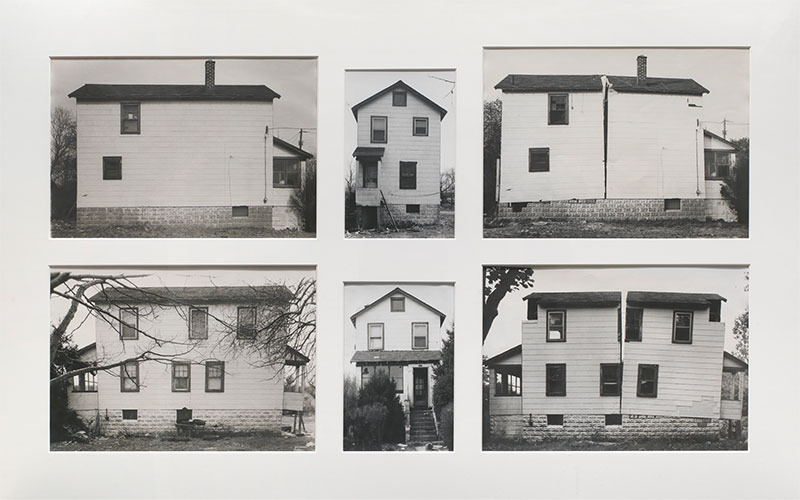

Similar moments of juxtaposition exist throughout New Jersey as Non-site, from Splitting, in which Matta-Clark literally destabilizes a house in Englewood, New Jersey (Figure 1), that was scheduled for demolition to make room for new development, to Gallery Transplant (1969), in which Dennis Oppenheim transposes the floor plan of an art gallery at Cornell University’s art museum onto a snow-covered lot in Kearny, New Jersey. In his 1973 film Landscape <-> Body <-> Dwelling, Charles Simonds buries himself in the derelict clay pits at Sayreville, New Jersey, which were at the time being closed and paved over for development; his body itself becomes the earthly surface on which he constructs elaborate miniature dwellings (Figure 2). Such contrasts check our nostalgia for decentered places against the realities of new technological landscapes, encroaching on and winning over natural ones. One hears the words of Marx throughout this exhibition, but also the voice of Antoine Picon, who shared the former’s sentiment: gone are the pictorial landscapes we once imagined, leaving only “anxious” landscapes like New Jersey, where ruins have been replaced by rust—ubiquitous reminders that there are no islands left.

Landscape – Body – Dwellling

The exhibition takes its name from Smithson’s

notion of the nonsite, the artist’s alternative to orthographic projections, which he lamented could only ever represent three-dimensional spaces in two dimensions. In other words, a nonsite is not a document or a stand-in for the original site so much as it is an access point. Many of the examples in the exhibition act as nonsites; careful to avoid illustration and interpretation, they provide impressions, maps, and remnants to visitors, who might themselves access these sites. This liminal position is found too in the examples where cooperative acts become literal expressions of another kind of threshold: between self and other, author and audience. Amiri and Amina Baraka’s Afrikan Free School (established 1969) in Newark and Nancy Holt’s

Stone Ruin Tours (1967–68), these represent instances where participants fulfilled the projects through direct involvement. This positioning is even more pronounced in the examples by George Brecht, Geoffrey Hendricks, Dick Higgins, and Robert Watts, who staged festivals, happenings, and performances throughout the state, namely at Rutgers University and George Segal’s farm in South Brunswick. (The donation of Segal’s archive to Princeton University in 2007–9 was the impetus for the show.)

The exhibition’s catalog makes the distinction between New Jersey as “place-bound site and as a de-located nonsite,” but the latter wins over in the exhibition itself. As its title suggests, this show frames New Jersey itself as a nonsite, leaving one in search of a corresponding site. This reinforces the tendency to consider decentered places always in terms of a center—in this case, New York—rather than as places in their own right.

The exhibition, like the artists therein, “produce[s] and exaggerate[s] this difference,” which is precisely what Marx would have the artist (and in this case, the curator) do: engender moments when we come to understand incursion all the more. But, like the nonsites in the exhibition, New Jersey is more than simply an “other place.” More than just a “non–New York,” New Jersey, as “de-located nonsite,” represents the transitive condition as site itself, one that brings us to terms with two seemingly oppositional landscapes. Neither the artists nor Baum bear a cynical approach to this liminal condition. If anything, the cynicism is directed at New York. Provincial in their own way, gallery-goers in the art world’s major centers are often unwilling to see past nonsites to sites themselves, to sites like those in New Jersey. One finds a kind of Sisyphus-like struggle in works like Michelle Stuart’s Sayreville Quarry History Book (1976). Despite her exhaustive collection of photographs and samples from the site, she is not nostalgic for Sayreville so much as driven to create some bridge between gallery-goers and the sites she knows they will not visit. The same cannot be said of this showing; visitors leave New Jersey as Non-site eyes open and excited to tour the state’s wealth of uncanny places.

New Jersey as Non-site too is a nonsite, maximizing the periphery as a place where we can perhaps more lucidly see the relationship between centers and noncenters. The exhibition showcases the role of Rutgers and Douglass Colleges in this regard, but the same can also be said about the work of Princeton University Art Museum and university galleries and museums more broadly, from the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University to the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, which have staged some of the most rigorous and timely exhibitions on related themes in recent years.