Alexander Robinson

Applied Research & Design

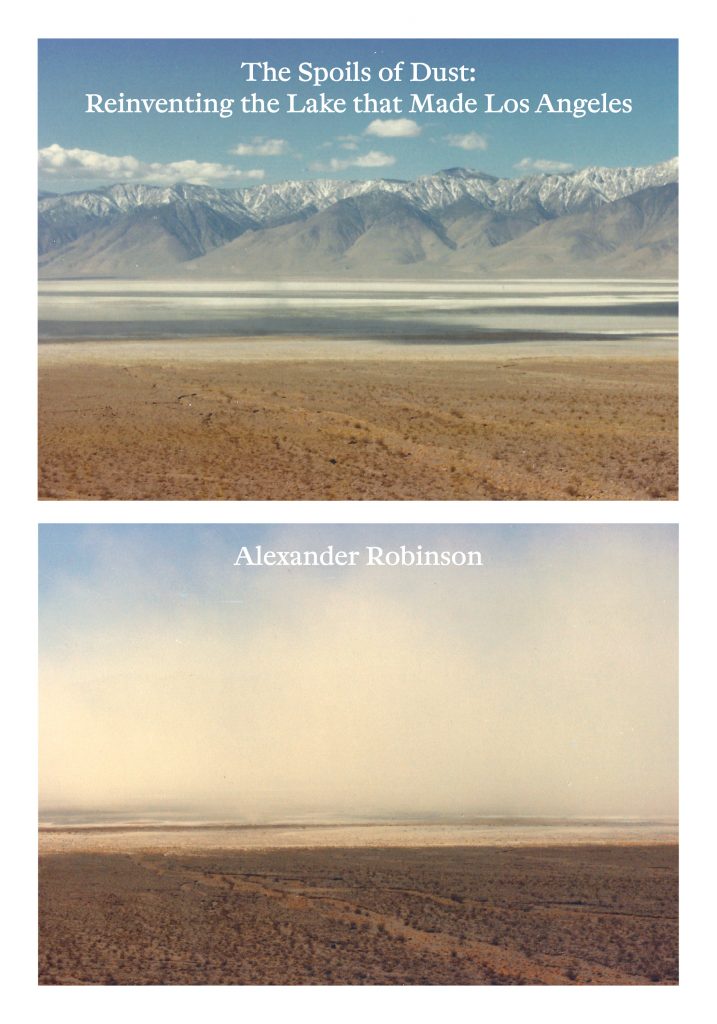

Outside of California’s water experts, few know where Los Angeles’s famous water grab came from or the social and environmental impacts that resulted. Alexander Robinson has written a thorough account of Owens Lake, which was once California’s third-largest water body. The Spoils of Dust: Reinventing the Lake that Made Los Angeles reads like a whodunit told by an omniscient narrator (Robinson himself, as a small-town detective), featuring the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District (GBUAPCD) and an unwitting protagonist, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). It is a compelling environmental saga that combines site analysis with a discussion of design process in the complex environmental and legal landscape that shapes Owens Lake today.

While Robinson invokes John McPhee’s 1993 Assembling California as the inspiration for his approach, this work resonates more with Jane Wolff’s 2003 Delta Primer: A Field Guide to the California Delta.1 Both Wolff and Robinson explore new ways of seeing and communicating the largely manipulated and fragile natural water systems that our modern lives depend on. Wolff’s series of hand-drawn playing cards depict 52 facets of California’s Sacramento River Delta, organized into four suits (garden, wilderness, toy, machine) to be shuffled and read in any order desired. Robinson presents Owens Lake through multiple prisms: water, dust, birds, and scenery; and in multiple timeframes: past, present, future. John McPhee, Assembling California (New York: Farrar Strauss and Giroux, 1993); Jane Wolff, Delta Primer: A Field Guide to the California Delta (San Francisco: William K Stout, 2003). His focus on ways of seeing and his fascination with infrastructure is an updated and timely take on J.B. Jackson’s love of everyday places.

A century ago, a famous engineering feat sacrificed Owens Lake for developers’ dreams. William Mulholland’s 200-plus-mile-long Los Angeles Aqueduct was key to developing Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley. Controversial from the start, the aqueduct intercepted melting Sierra Nevada snow, sending it south before it reached Owens Lake. The lake shrank and began to dry up, disrupting the lives of Native Americans, farmers, and abundant and diverse wildlife populations. The water helped Los Angeles grow seven times over in twenty years. The crusty lakebed soon was the source of the world’s largest dust emissions. It took decades until a way to hold LADWP accountable appeared. LADWP built the Second Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1972, diverting nearly all surface waters from Mono Lake, dropping lake levels by half and doubling its salinity in ten years. In 1979, lake advocates sued LADWP for violating the Public Trust Doctrine. The California Supreme Court agreed and ruled that LADWP had to conserve Mono Lake above a certain level, and that the state’s duty to protect the public’s common watery heritage extended to Owens Lake.

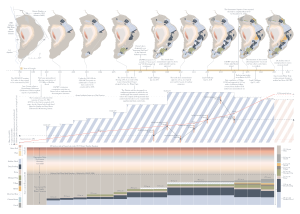

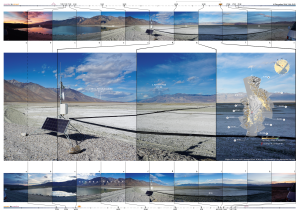

The GBUAPCD’s extensive dust mapping and documentation, and LADWP’s attempts at finding waterless solutions to meet the public trust, make up the bulk of Robinson’s maps, figures, and text. He organizes the book around the idea of a prism, directing our gaze through the multiple refractions of a single view. While each refraction is fascinating, it is dizzying at times to find a thesis or follow a thought. The clearest concept is the accidental remaking of a watery and welcoming habitat. With the mandate to mitigate dust, the GBUAPCD’s personal dust observations and detailed maps showed beyond a doubt that the dried lakebed was in fact the source of dust. LADWP eventually had no choice but to re-introduce water to the lake.

Robinson critiques the missing human scale and grounded sensory experience in the engineered designs for Owens Lake. He appreciates the more recent contributions of landscape architects in the form of viewing stations reminiscent of the land-art movement and water-wise dust mitigation alternatives integrating operational, ecological, and experiential goals. But even these, he writes, are just a beginning. He references the missed opportunity presented by the largely ignored, multipurpose, integrated 1994 Master Plan for Owens Lake led by John T. Lyle in Cal Poly Pomona’s 606 studio.

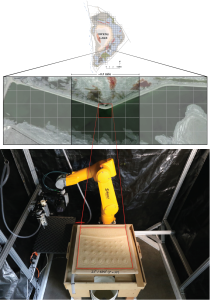

Robinson’s book moves through the GBUAPCD and LADWP perspectives before proposing his own approach to analysis and design. A sand printer connected to a parametric digital modeler enables him and his students to shape the sand into patterns that can be projected upon.

The modeled topography is laser scanned and fed into software that analyzes it for dust control scenarios which it projects back onto the landforms. The user then sees an image on screen depicting what the topography would look like at Owens Lake. The Rapid Landscape Prototyping Machine allows Robinson and his students to explore dust mitigation landforms that might suit the dry lakebed and reduce air pollution without the use of water. He transformed this machine into an arcade-style game, a riff on the technocratic design process that too often destroys healthy social and environmental processes.

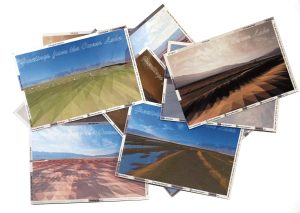

This “Greetings from Owens Lake” ending feels like another scratch on the surface. Robinson has listened and studied, explored and perused. [Insert figure 6] The arcade game and The Spoils of Dust are beautiful depictions of the missing Lake and the first engineered measures to begin restoring life to the Owens Valley floor. Reflecting the aesthetic public trust values that drove the lake’s restoration, the work is appropriately visual. But it left me wanting more. Lyle’s process begins with the Stage of Romance—a design phase for gathering information and questioning the site, its context, listening to its people, and learning about its history and its systems. Robinson’s “Greetings from Owens Lake” reads like an artwork in the vein of Lyle’s Stage of Romance. It is a beautiful love letter.

Here Robinson’s timely discussions around air pollution and public health, birds as indicators of ecosystem health, and the urgent case for water as a common good, give way to his central concern: the design process itself. Robinson compiles a beautiful array of view diagrams, maps, and plots of human versus industrial design scale. But by the end I felt I was drowning in academic design-speak when what I wanted was a sense of how we could leverage the legal precedent to apply to other water bodies—even our oceans.

As we grapple with life amid the COVID-19 pandemic, we face questions and inequities that are very much at the heart of Robinson’s subject. Even before the pandemic forced us to reconsider the reliability of imported goods, climate change and reduced snowpack forced Los Angeles to rethink its imported water supply. Mayor Eric Garcetti’s 2019 Sustainable City pLAn proposes increasing local water supplies from 15% sourced locally between July 2013 and June 2014 to 70% sourced locally by 2035. While designing and implementing new infrastructures, there are sure to be similar conflicts between big interests and small, single-purpose and integration, engineered versus nature-based. The Spoils of Dust is perhaps a prelude to a heavier tome on the deep connections between water for drinking, water for farming, water for profit, and the watery ecologies that we and our fellow creatures depend on for survival. With his expertise in infrastructure and living systems, Robinson is well poised to write it.

Endnotes:

Claire Latané designs, writes about, and teaches community-led, nature-based design strategies. Her book Schools that Heal: Design with Mental Health in Mind will be published by Island Press in 2021. She is an Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

How to Cite This: Latané, Claire. Review of The Spoils of Dust: Reinventing the Lake that Made Los Angeles by Alexander Robinson, JAE Online, August 14, 2020.

All images used in this review are credited to the author’s website:

https://oorscapes.com/The-Spoils-of-Dust-Reinventing-the-Lake-that-Made-Los-Angeles.