Essay

JAE Fellow

I.

I only found Chinese diaspora in the Sanborn Maps because I was looking for oil.

As a practitioner trained first in Western art and secondly in Western architecture, I have been looking—for, at, with, from, in light of, in spite of—in very particular ways for some time. While I am licensed in California to build, and there is much building needed, I am pulled equally to unbuild: to understand how disciplinary tools of architecture have been used historically to construct, uphold, and reify existing systems of oppression, and how they might instead be used to unveil, imagine (to look), and otherwise draw forth futures beyond.

I’m also looking as a Mandarin-speaking Chinese-diasporic person1 whose family lives on both sides of the Pacific Ocean, in mainland China as well as in the continental US. There is a body (mine), looking, whichever trainings and teachings it has received. It follows that much of how I approach my work involves translations across diaspora, and it all tends to converge in one particular painting (Figure 1).

Figure 1. 张择端 Zhāng Zéduān, 清明上河圖 Along the River During the Qingming Festival, 1085–1145 CE. (click to view)

Over five meters long, this scroll painting by eleventh century artist 张择端 Zhāng Zéduān, titled 清明上河圖 Qīngmíng Shànghé Tú or Along the River During the Qingming Festival, was painted nearly 1000 years ago. My attempt to show you the extents of the work within these margins results in us not being able to see it at all, and that may be precisely the point. Scroll paintings were in fact choreographed to be unveilings, unravelings of a spatial-temporal narrative in which the viewer is able to freely move around the work, shifting the view itself, rather than moving in front of a view already fixed.

Figure 2. 张择端 Zhāng Zéduān, 清明上河圖 Along the River During the Qingming Festival, 1085–1145 CE. (click to view moving image)

In words more familiar to those of us with architectural training: parallel projection allowed 张择端 Zhāng Zéduān and other East Asian artists to create expansive, sweeping visual and spatial analyses of class, gender, geography, and daily life with great precision (Figure 2). As well, in East Asian painting traditions, text was often incorporated as poetry to heighten the experience, in this case suggesting a long journey upriver home to care for the tombs of ancestors. Earlier this year, my mother made her way home to 安徽 Anhui for the first time since 2019 to bury her father, who left us before Chinese diaspora were allowed to return,2 in time for 清明节 Qīngmíng Jié, the Tomb Sweeping Festival. All of these sweeping translations of landscape into meaning—I was taught this by my Chinese-diasporic family, but to no surprise, neither in art school nor architecture school in the US.

In Western schools, I would not ever be taught the Mandarin for parallel projection, 等距透视 děngjù tòushì, but I would learn from Chinese children’s shows after school the term, 宇宙 yǔzhòu, meaning, generally speaking, universe. Taken apart, the two words by themselves mean, respectively, “space” and “time,” because in traditional Chinese cosmology dating to 2000 years ago, the universe has always been simply space-time as one continuum. This cosmology and the representational tool of parallel projection emerged contemporaneously, informed one another greatly, and certainly might explain to us today why humans in the first century might have thought this would be a fun way to draw.

While cultures across the world have used axonometries throughout time, sixteenth and seventeenth century Jesuit missionaries expedited exchanges of East Asian parallel projection from the East to the West,3 along with silk, tea, gunpowder, paper, and spice. As historian Lisa Lowe describes, these imperial and colonial encounters were deeply and intimately connected to, and spurred, the same imperial and colonial encounters across the Atlantic in search of another route to India and China, gold, glory, and the expropriation of Indigenous and African sovereignty.4 By the time it is documented in the West by William Farish, who in 1822 writes “On Isometrical Perspective”5 to explain the utility of this representational tool in an industrializing Britain, there is no mention within his claim of authorship of any significance elsewhere, cultural or cosmological.

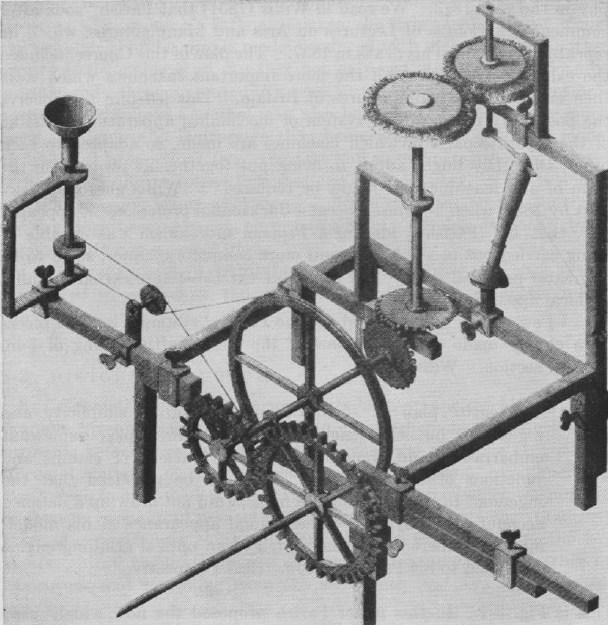

Figure 3. William Farish, optical-grinding engine model from “On Isometrical Perspective,” 1822.

In this way, drawing-as-cosmology becomes displaced over space and time into a representational tool for describing machines in service of capital (Figure 3). This isn’t to romanticize (and therefore flatten) the many origins of parallel projection, but to, in these same margins, give breathing room to the scale of how many diasporic translations of ideas have nestled up atop one another in our bodies and in the spaces we inhabit.

II.

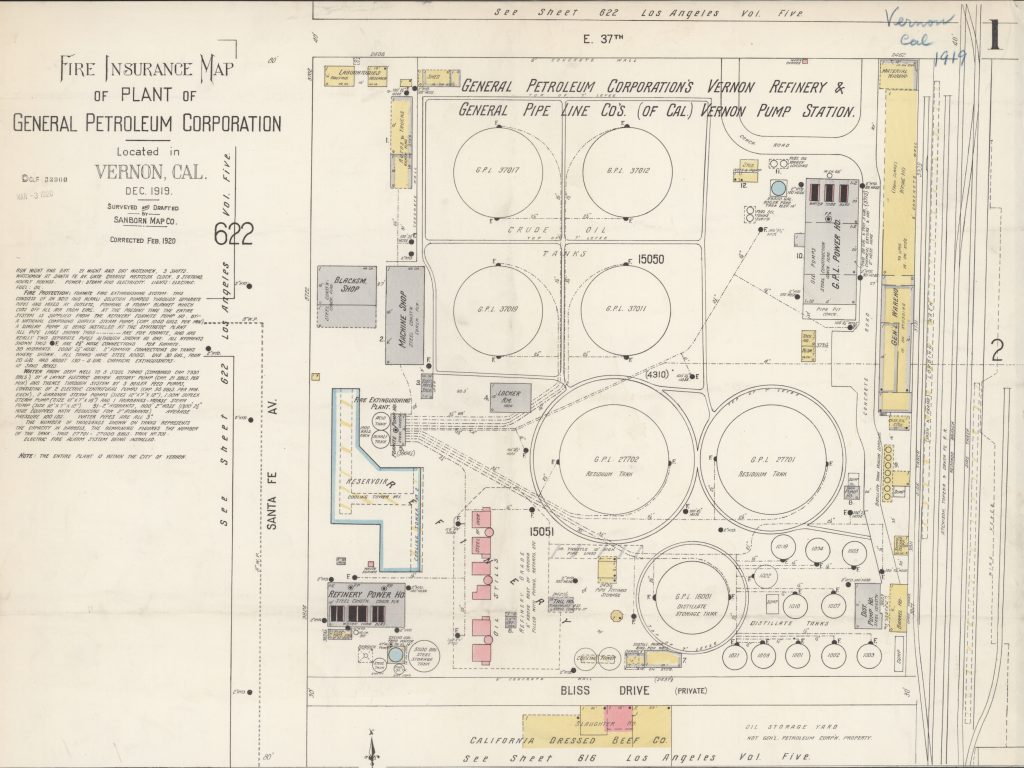

Regardless of the project, architects create documents that facilitate translations and transitions between past, present, and future. These documents—by which I mean drawings, specifications, contracts, schedules, diagrams, photographs, and other visual artifacts—play an outsize role not only in physical construction, but in cultural construction—particularly through historical and legal records. For instance, this Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from 1919 is one of the only detailed plans of a petroleum plant design available to the public today, following the inaccessibility of both institutions (governments, industries, and their archives) and of the drawings themselves, which can be purposefully difficult to read without specialized training (Figure 4).

Figure 4. 1919 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of General Petroleum Corporation, Vernon, Los Angeles County, California. Tongva lands. Library of Congress.

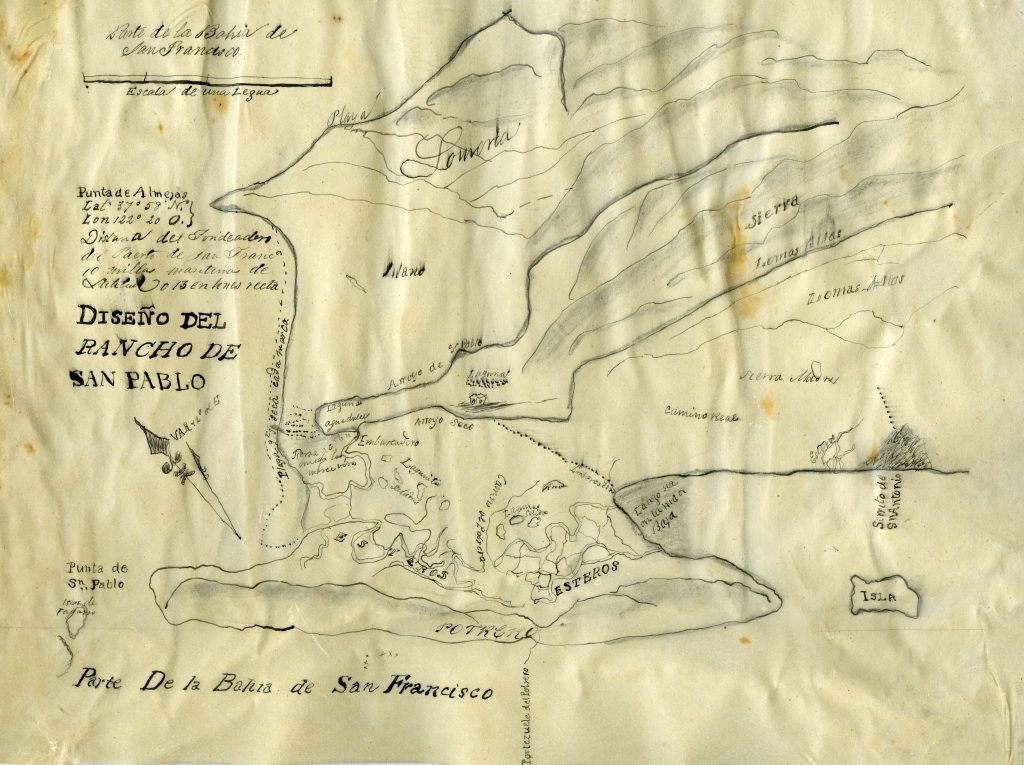

Significantly, this was documented, not because of educational foresight, but because of a lucrative desire to assess fire risk and thus insurance value. The ways in which this Sanborn surveyor looked at and represented this site of extraction through linework and negative space create colonial footprints, or what Cruz García and Nathalie Frankowski describe as historical narratives that, like propaganda, “satisfy the positions of settler-colonization, ruling classes, capitalism, white-supremacy, and heteropatriarchy.”6 In the case of this Spanish colonial diseño of Rancho San Pablo (present-day Contra Costa County), to “design” Ohlone and Miwok lands was quite literally to signify the boundaries of settler colonial land theft (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Former lands of Mission Delores, or San Pablo, or Cuchiosmos, or Cuchiguenos, or Cuduyunes Rancho, 1834. Ohlone and Miwok lands. California State Archives.

It is therefore both incredibly powerful and dangerous to make these documents, as unequal documentation has not only contributed to white supremacist and settler colonial structures and systems, but has perpetuated their mythologies and exacerbated their erasures. “You reproduce something by stabilizing the requirements for what you need to survive or thrive in an environment,” Sara Ahmed points out,7 as architects continue ad nauseam to reproduce certain representations and ideas of space at the expense of the possibility of others. “The more the path is used, the more the path is used.”8

Meanwhile, our experiences of global petrochemical empire are embodied in every sense: pipelines through ancestral sites, refineries along our beaches, pumpjacks on our street corners, wells across from our bedroom windows, and chemicals in our lungs. While their spatial violences are indisputably embodied, the scales, forms, and boundaries of these architectures of extraction are often intentionally obscured and thus difficult to dismantle. My practice and research thus wonder aloud about representations of violence and the violence of representations by asking questions both using and about architectural tools.

Figure 6. Photo and video of McKittrick Tar Pits in Kern County, California, Chumash and Yokuts lands. Photograph and moving image by author. (click to view moving image)

The first time I saw a real live seeping tar pit—outside Bakersfield, California, where Yokuts and Chumash communities have used tar for millennia (Figure 6)—I was so surprised at how earthly it looked and sounded and smelled and felt. I had an uncanny desire to taste it, too. It was a reminder of what Métis scholar Zoe Todd writes, that oil is kin—that these fossil former beings are not themselves harmful, but rather, “the ways that they are weaponised through petro-capitalist extraction and production turn them into settler-colonial-industrial-capitalist contaminants and pollutants.”9

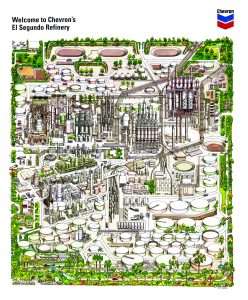

Architecture’s visual strategies can be quite good at seeing and understanding entanglements at both systems and body scales. But whereas folio depictions of Western European mineral extraction in Diderot and D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie (1768) show geological details and vignettes above and below ground through sectional perspectives (Figure 7)—and even 200 years later, Standard Oil, now Chevron, itself commissioned a plan oblique for its promotional materials (Figure 8)—today, it is hard to come by representations of sites of extraction that are not stylized or abstracted from above.

Figure 7. Diderot and D’Alembert, “Mineral Lodes or Veins and their Bearings,” from Encylopédie, vol. 6, 1768; Figure 8. Chevron promotional booklet, undated ca. 1970. Tongva lands. El Segundo Historical Society.

I started making my own drawings of oil landscapes—crude representations, if you will—because in researching sites of extraction and resistance, I regularly found that most existing representations (architectural and otherwise) are neither accurate nor precise about adjacencies, and thus could not become accurate or precise about their impacts. When oil infrastructures are adjacent to our homes and communities (as they always are at some scale), these documents tend to not include both places at once—or to otherwise misrepresent spatial violence. For instance, an image search for Point Molate Beach and the adjacent Chevron refinery in Richmond, California yield photo-narratives of place that seem worlds apart—and yet these two places are only imagined as separate but are really one petrochemical landscape.

As Richmond organizers and residents fighting environmental injustice can attest,10 this is a harrowing and dangerous oversight with extreme harms done to communities and ecosystems. Since the 1990s, along with Communities for a Better Environment (CBE) and other environmental justice organizations, the Asian Pacific Environmental Network (APEN) has organized refugee and immigrant communities, primarily Laotian and Southeast Asian, against environmental health violations committed by Chevron and their agents. Confronted with what Nicholas Mirzoeff describes as “complexes of visuality,” which visualize history to enable claims to authority,11 I follow the work of radical thinkers and organizers like APEN and CBE in trying to exercise a right to look—and the right to visualize our own histories.

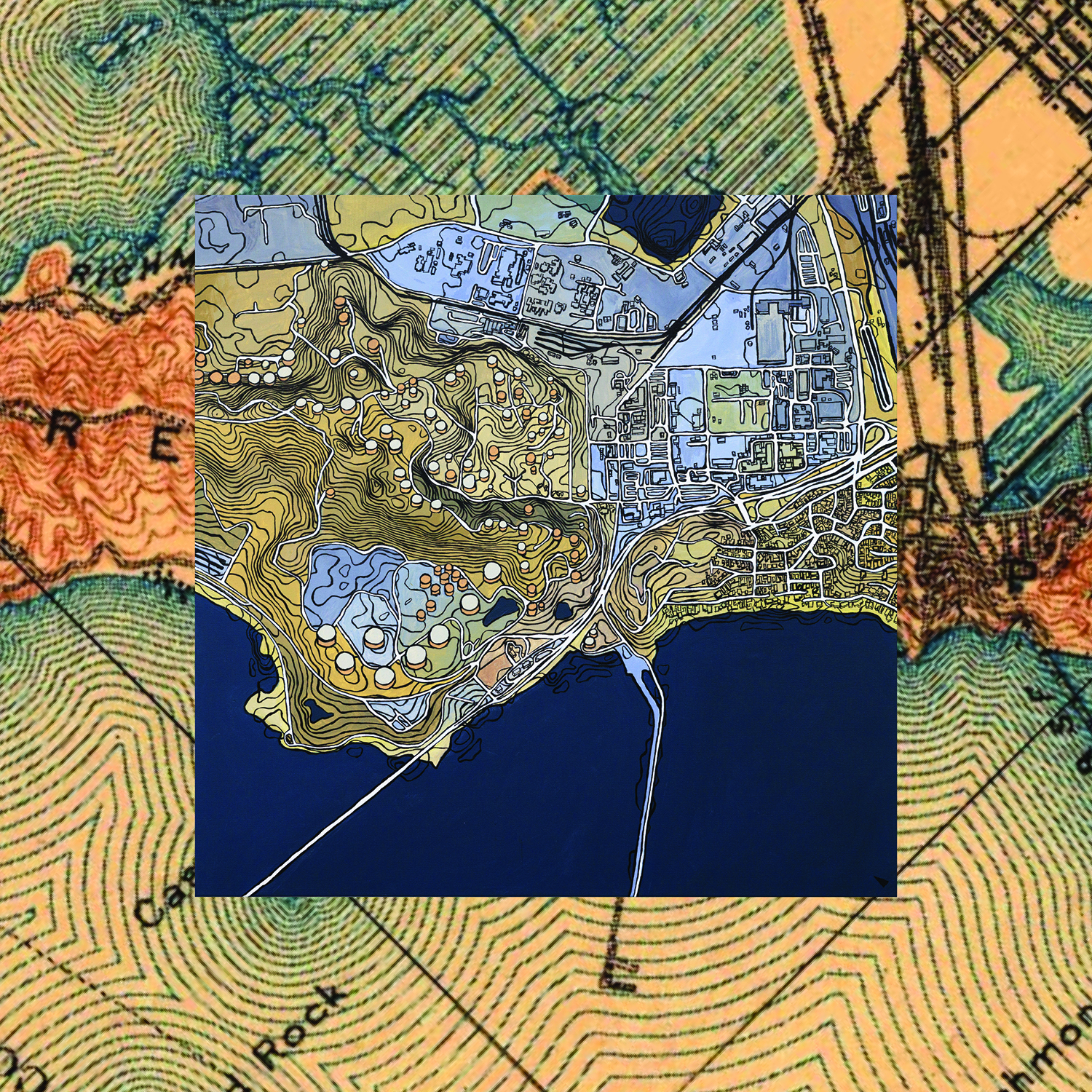

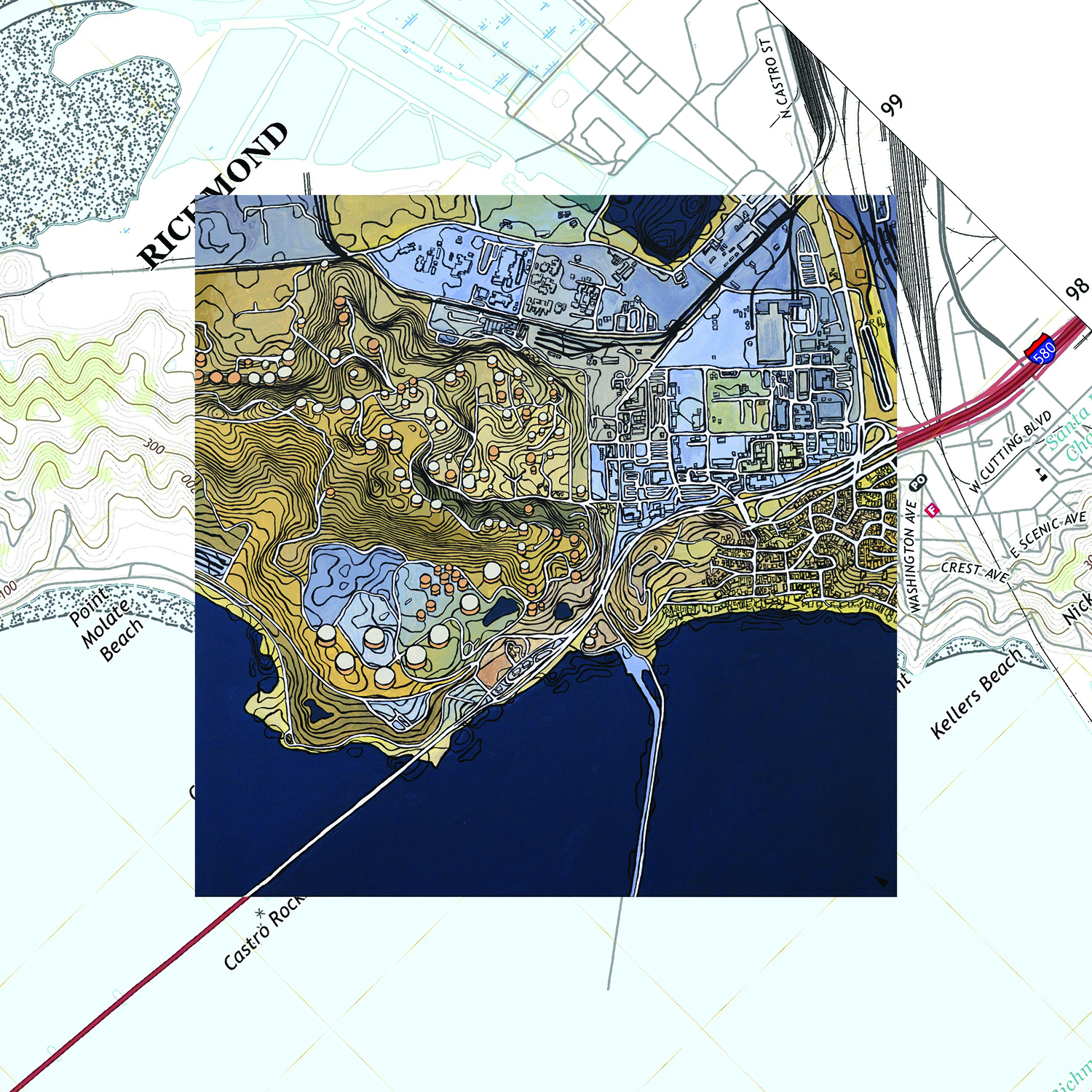

One of my most recent works, Crude Neighbors: Chevron Refinery, Richmond California, is a 36-by-36-inch acrylic on canvas painting of the refinery in Richmond, on Ohlone and Miwok lands, the first refinery built by Standard Oil in California (Figure 9). Although, insofar as acrylic paint is a petroleum product, I’ve started to more truthfully refer to it as an “oil painting.” The work is set to a scale, meaning every one inch represents 250 feet, and it employs axonometry, in this case, oblique parallel projection, historically an East Asian landscape painting technique, later co-opted by Western architecture for military and industrial use. If it sounds a bit convoluted to create a landscape painting at an engineering scale in a projection that comes from both Chinese art and Western architecture, it is perhaps in that messiness that I seek some kind of clarity.

CalArts REEF Artist-in-Residence in downtown Los Angeles. Tense Renderings

CalArts REEF Artist-in-Residence in downtown Los Angeles. Tense Renderings

Figure 9. Bz Zhang, Crude Neighbors: Chevron Refinery, Richmond, California. Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 36 inches, 2022. Ohlone and Miwok lands.

I could make this painting by translating and projecting two- and three-dimensional data, integrated from publicly available sources like OpenStreetMap, NASA, the US Geological Survey, and so forth. These tools of architecture can approximate real-world spatial conditions with remarkable precision, so that we see representations of buildings and freeways and railways and the contours of the land. However, this precision is only as good as the data we put in. Whereas publicly available sources attempt to give us the reality of built structures, they do not (and could not) show us everything. As designers (from the Latin designare, to designate), we strive to represent the stories and spaces that interest us and fail to represent those that do not. Oil infrastructures, or the spatial typologies of what Neeraj Bhatia describes as the “surfaces, containers, and conduits” running through our cities and landscapes,12 so often do not. Although seen from above in satellite imagery, these oil infrastructures are conspicuously absent in publicly available linework, which turns out to not be accurate at all (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Bz Zhang, Crude Representation(s): Chevron Refinery, Richmond, California, 2022. Layers of linework compiled by author using OpenStreetMaps, NASA, and US Geological Survey files representing Richmond, California, Ohlone and Miwok lands.

Today, this satellite image is usually how we, the public, would see sites of extraction (Figure 11), and this bird’s eye, which itself has roots as a military technology, distorts our relationship to them, hindering our understanding of how they work and the types of spatial violence they may be inflicting. This refinery in particular is notorious for toxic gas flares, spills in the San Francisco Bay, and even explosions.

Figure 11. Bz Zhang, Crude Representation(s): Chevron Refinery, Richmond, California, 2022. Acrylic painting behind 2022 Google Maps satellite image of Richmond, California, Ohlone and Miwok lands.

We think of architectural linework or satellite imagery as more technologically advanced and thus more accurate, while we assume paintings, for instance, are not. Perhaps this is mostly the case, but when we see blank gray fills instead of oil infrastructures in municipal zoning maps, with which the city of Richmond determines lawful land use, it becomes clear that something huge has been missed in the accuracy of its visual representation and its accountability to the public.

Figure 12. Bz Zhang, Crude Representation(s): Chevron Refinery, Richmond, California, 2022. Acrylic painting framed by 1915 US Geological Survey map of Richmond, California, Ohlone and Miwok lands.

In the first US Geological Survey map of Richmond in 1895, we can see that what was once wetland ecosystems in kinship with Ohlone communities is today an infilled network of pipes, railways, tanks, boilers, and tailing ponds. On the edge of a subsequent 1915 geological survey (Figure 12), we can see that Point Molate was actually the site of a Chinese shrimping village, one of dozens found across the San Francisco Bay between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, from Richmond to West Oakland to Marin to Hunters Point, of which only one exists today. And, having been founded in 1902, we can also already see Standard Oil’s pier, from which Chevron still today receives oil tankers.

Figure 13. Bz Zhang, Crude Representation(s): Chevron Refinery, Richmond, California, 2022. Acrylic painting framed by 2021 US Geological Survey map of Richmond, California, Ohlone and Miwok lands.

Only the pier remains visible in the most recent publicly available USGS map of Richmond, from 2021, which uses the same pale blue fill to code both toxic tailing ponds in the refinery yard at the top of the image and the San Francisco Bay water on the bottom and omits any other markings that would indicate the presence of oil (Figure 13). But most of us are not looking at maps by the USGS to move through the world. Most days, we might all be looking at one particular map from Alphabet, which applies the same representational logic. Just as freeways on Google Maps are flattened to approximate surface roads, which softens our perception of their violent past and present, oil infrastructures melt into soft grays and blues, as if they weren’t even there.

Figure 14. Bz Zhang, Crude Representation(s): Chevron Refinery, Richmond, California, 2022. Acrylic painting framed by maps of Richmond, California, Ohlone and Miwok lands: 1895 US Geological Survey, 1915 US Geological Survey, 2016 municipal zoning map, 2021 US Geological Survey, 2022 Google Maps. (click to view moving image)

Across time and space, these strategies for obscuring complex systems are, as we know, by design (Figure 14). At the core—and often contractually—we reproduce systems of oppression by stabilizing them in documents through claims of neutrality, through our omissions, our complicitness, through our carelessness. As reported by Stand.earth and Amazon Watch, half of the Amazonian crude oil extracted and exported from Ecuador, where Chevron famously was sued over an oil spill in 2011, comes to California.13 With the San Francisco Bay and Los Angeles as critical nodes, the flows of oil and capital crisscross borders and oceans, creating a continuous oil landscape and continuous frontline.

But tools come from many space-times and can be used in many other ways. As Macarena Gómez-Barris has described, we can “utiliz[e] the same technologies of research and digital output that corporations use [and yet] divert and repurpos[e] them to deauthorize the extractive view.”14 In disentangling representational tools of Western art and architecture—the so-called “master’s tools”—from what Audre Lorde terms “the master’s concerns,”15 I am following practices of Indigenous, Black, and decolonial countervisualities, from collective mapping by the Native Lands Advocacy Project, the Watch the Line Project made by coalitions to Stop Line 3, to Imani Jacqueline Brown’s Unraveling Industry: Follow the Oil project mapping petrochemical landscapes in Louisiana. In particular, I look to the trans and nonbinary and queer and woman and disabled and worker futurities within them that have each distinctly and collectively resisted extractivism of lands and bodies for centuries.

III.

While Crude Neighbors, the “oil painting,” was being exhibited in Los Angeles,16 I was driving to an artist residency halfway across the continental US and stopping by more sites of extraction along the way: the Hoover Dam bisecting the Colorado River in Nüwüwü and Hualapai lands; silver and gold and copper and salt mines across California, Nevada, Utah, and into Colorado. In doing so, I followed the waters stolen every day by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power up to their source in Colorado, and I tumbled down the other side into the Mississippi River watershed, where the South Platte River led me to my new temporary home.

But curious things had been happening for a while. The year before, while accompanying Mexican-American and French-Tunisian artist Red Rotkopf in his research and photography on California settler colonialism, we turned a corner from the Misión de Santa Bárbara, on Chumash lands, and found ourselves unexpectedly in front of a cocktail bar, still wearing its first name, “Jimmy’s Oriental Gardens,” in an old Chinatown I’d never heard of. Another time, at an abandoned borax mine in Death Valley, Western Shoshone lands, I squinted to see the unmarked ruins of housing for Chinese laborers in the flats below, which had been noted only in passing on the interpretative sign. Now, in Denver—Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, and Oceti Sakowin lands—where I stopped to eat banh mi at my sister’s favorite spot, I visited the wall downtown where a plaque had just been removed because of its racist and derogatory language placing blame on Chinese residents for the 1880 race riot carried out against them (Figure 15).

Figure 15. Location of former plaque memorializing the so-called “1880 Chinese Riot,” which was an anti-Chinese race riot instigated by white residents of Denver, Colorado, on Cheyenne, Arapaho, Ute, and Oceti Sakowin lands. The white mob of about 3,000 burned down Chinatown, killed one Chinese man, and wounded others. None were held accountable. It is not a coincidence that the removal of the plaque and official apology has been overseen by Mayor Michael Hancock, Denver’s second Black mayor. Photograph by author.

The message I read on this wall was: There is a body (mine), looking.

In her book Ornamentalism, Anne Anlin Cheng offers a feminist theory for the “yellow woman,” whose peculiar experiences both intersect with and depart from other racialized and gendered subjectivities surviving between personhood and objecthood. To survive in Western, white supremacist spaces in a body that is Asian and femme is to be “[s]imultaneously consecrated and desecrated as an inherently aesthetic object.”17 It is from this vantage point that I have been sitting with a set of Chinese phrases, permeating across the Pacific since our first encounters with Westerners: 丢脸 diūliǎn, to lose face; 保全面子 bǎoquán miànzi, to save face; 给面子 gěimiànzi, to give face; even 要 yào or 不要脸 bùyào liǎn, to want or to not want face. There are at least a dozen other turns of phrase describing the demonstration of respect, deference, or the failure thereof, and even a line in Alice Wu’s iconic queer Asian film, “Saving Face,” from 2004, in which father says to daughter, “我这辈子的脸被你都丢光了 Wǒ zhè bèizi de liǎn bèi nǐ dōu diū guāngle! You have lost me my entire lifetime’s worth of face!”18

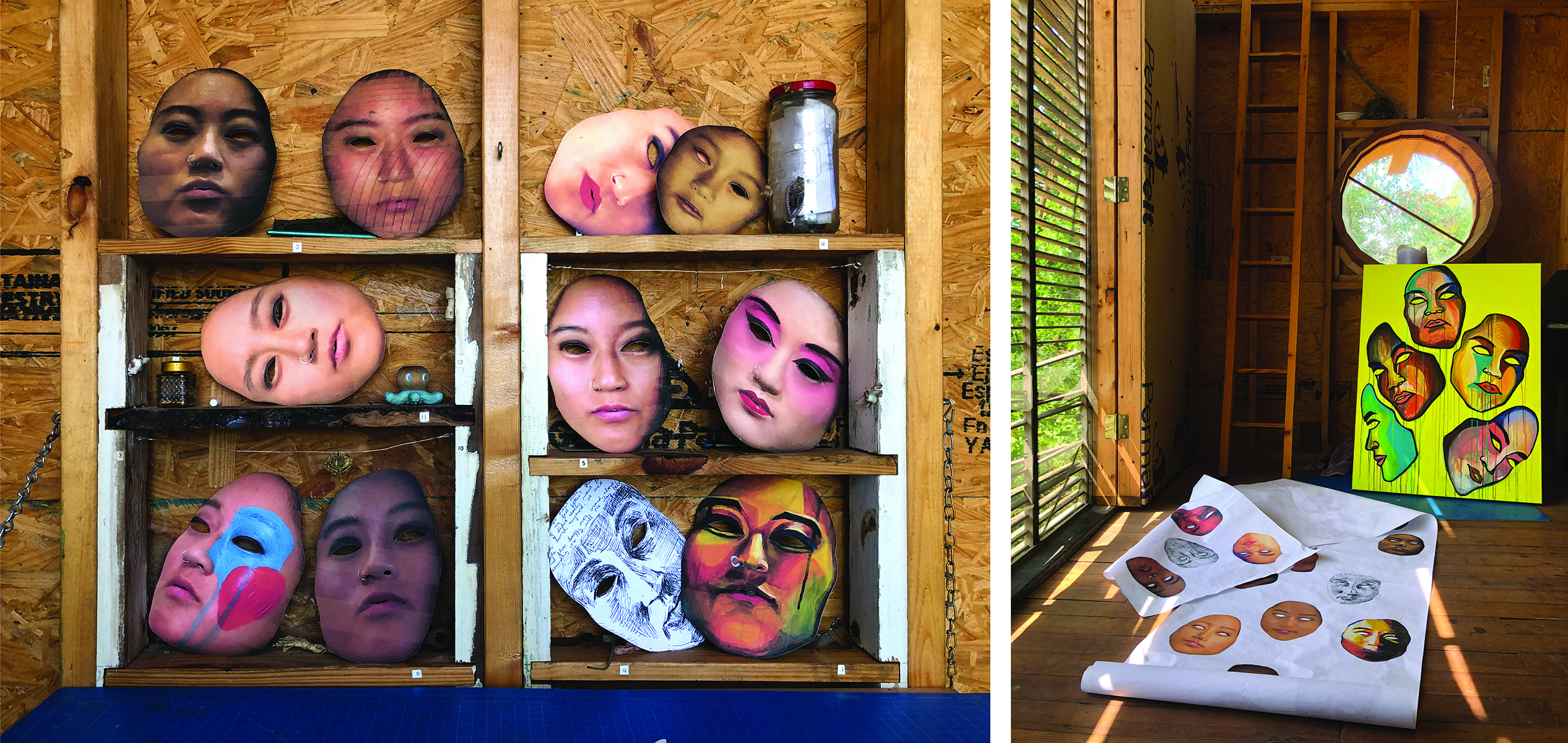

Figure 16. Details from Bz Zhang, 丢脸 diūliǎn / lose face series while artist-in-residence at Art Farm (Marquette, Nebraska), 2022. Oceti Sakowin and Pawnee lands. Photographs by author.

In Nebraska, Oceti Sakowin and Pawnee lands, I worked from this focal point in hopes of physically, culturally, and emotionally excavating experiences of shame, dysphoria, agency, and identity through a queer trans Chinese-diasporic lens, by literalizing these actions taken upon a face (Figure 16). Particularly through the eyes of this “yellow woman,” who lives within my body even as I do not self-identify as yellow nor woman, I asked: Who owns a face, whose is it to lose or to save, and where has it gone when lost? As “someone too aestheticized to suffer injury but so aestheticized that she invites injury,”19 how does one—borrowing from trans and queer Black and Brown ballroom culture—serve one’s own face instead?

By chance, this artist residency was a stone’s throw away from the eastern terminus of the first transcontinental railroad in the United States, in Council Bluffs, Iowa, which I visited dutifully, and by chance, I had planned to drive along I-80 to my next engagement, at the western terminus in Gauh Gāmsāan (旧金山, Jiùjīnshān, San Francisco). Tracing this route, I left paper masks—lost my faces—one by one at sites of Chinese diasporic settlement. I was traveling forwards on the colonizer trail to California and yet meeting the ghosts of my ancestor-cousins living and working and inevitably loving themselves and others inland, and thus somehow I was going forwards and backwards at the same time (Figure 17).

Figure 17. Details from Bz Zhang, 丢脸 diūliǎn / lose face series while artist-in-residence at Art Farm (Marquette, Nebraska), 2022. Oceti Sakowin and Pawnee lands. Moving image by author. (click to view moving image)

Figure 18. Details from Bz Zhang, 丢脸 diūliǎn / lose face series while artist-in-residence at Art Farm (Marquette, Nebraska), 2022. Oceti Sakowin and Pawnee lands. Photograph and moving image by author.

It finally occurred to me that in my makeshift procession along this haunted infrastructure, I had not been losing my face in all those gestures, but perhaps giving it to—meaning to show due respect for—ancestor-cousins of mine along the railway (Figure 18). The faces aside, I was still looking for more sites of extraction hidden in the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps when I stumbled across one word a dozen times, then a dozen more, and more again: “Chinese,” a word which looks and sounds nothing like our many words for ourselves—scrawled across maps made by an Anglo-American company to finesse capital out of fire. These maps are well-known to architects as a time capsule of nineteenth and twentieth century US cities and towns for our reference, but they were in fact created by and for Anglo-Americans to sell fire insurance policies from urban centers based on a surveyor’s assessment of hazard. And while these maps were never made with non-white communities in mind, nor for their safety, nor their participation, at site after site of nineteenth century extraction, I found traces of Chinese diaspora in handwritten capitalized letters.

The sites I was now tracing had been inscribed and reinscribed into land by a succession of US white settler colonial infrastructures: the California Trail (established 1811–1840), the First Transcontinental Railroad (constructed 1862–1869)—which exploited Chinese bodies and labor to dispossess Indigenous peoples and lands and to suppress Black resistance and liberation20—and finally, Interstate 80 (constructed 1956–1986). Their sequence was, incidentally, traced again in 1988 by recently arrived Chinese students, my parents in the Beautiful Country (美国 Měiguó USA), and, suddenly, in 2022, by me, searching.

Looking and searching became 给面子 gěimiànzi—giving face—to Chinese-diasporic informal architectures across the continental US, outside of all the major cities where we’d expect them. In some cases, there is one remaining building—such as in Truckee, California, where Chinatown was destroyed three times, and the last remaining building, an herbal store, is now an office for an interior design firm—or perhaps a reconstructed facsimile as a museum, as in China Camp State Park, where I was sharing the view with a white wedding party in Marin County. In others, there is just one street sign—as in “Plum Alley” outside of a parking garage in Salt Lake City, Utah, or “Ahsay Avenue” named for a Southern Chinese labor organizer in Rock Springs, Wyoming (Figure 19). While I ran out of paper masks of my own face to leave behind, I continued taking with me photographs on my phone, oriented and cropped as if documenting progress on a job site. Truthfully, these are ongoing sites of construction. As bell hooks wrote of Black cultural genealogies of resistance, “the vernacular is as relevant as any other form of architectural practice.”21 Up and down Main Street in Lohk gēui jan (樂居鎮, Lèjūzhèn, Locke, California) in Sacramento County, the largest surviving rural Chinatown, the material histories of the “vernacular” (and its historic preservation or lack thereof) speak plainly of cultural legacies, politics of land ownership, and the coevolution of multiethnic communities.

Figure 19. Clockwise from top left: Truckee, California, Washoe lands; Marin County, California, Coast Miwok lands; Salt Lake City, Utah, Eastern Shoshone and Goshute lands; Rock Springs, Wyoming, Eastern Shoshone and Cheyenne lands; Walnut Grove, California, Lisjan Ohlone and Plains Miwok lands; Santa Barbara, California, Chumash lands; Locke, California, Lisjan Ohlone and Plains Miwok lands; Evanston, Wyoming, Eastern Shoshone lands; Locke, California, Lisjan Ohlone and Plains Miwok land. Photographs by author.

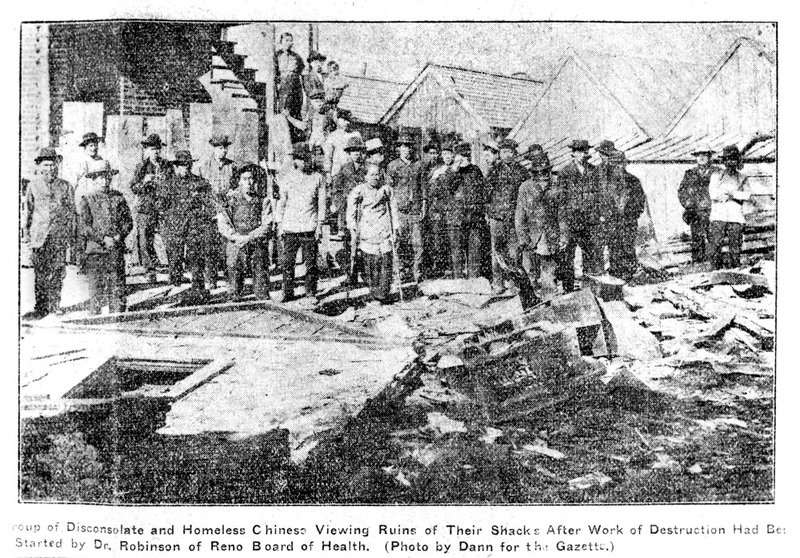

But in nearly all cases of rural Chinese diaspora in the US West, Chinatown was purposefully set on fire and burned to the ground, as in Reno, Nevada, where it was burned down at least twice, the second time by the Reno government (Figures 20 and 21). Locke was only founded after the Chinatown of nearby Walnut Grove was consumed by flames in 1915. And so, in nearly all cases of Chinatown burned to the ground, I continue to look for and find traces of us in the insurance maps they drew in case of fire.

Figure 20. Ruins of Chinatown in Reno, Nevada, 2022. Washoe and Northern Paiute lands. Photograph by author.

Figure 21. Ruins of Chinatown in Reno, Nevada, 1908. Washoe and Northern Paiute lands.

In engaging Sanborn maps, which most often labeled Chinese structures as hazards, as seen in the green highlight of Chinese-owned laundries in San Rafael, California, I used translation to reconstitute Chinese diasporic structures—or, in truth, a phantom or shadow of them—out of the technical details left by Anglo-American surveyors: 1-story or 2-story; stove pipes or terracotta or brick chimneys; composite or shingled roofs, fire walls, and so forth (Figure 22). There are virtually no other architectural documents of these Chinese diasporic settlements, and yet, translating what is on the page only reveals the limits of translation, in what truths are not there.

Figure 22. Giving face to ancestor-cousins in 1887 Sanborn map of San Rafael, California, Coast Miwok lands. Animated image by author.

These architectural pasts and presents reflect the calculus of white supremacist settler colonization in time and space—on the one hand, “The Chinese Must Go!” (a rallying cry originating in the 1870s in California, in many ways the birthplace of anti-Asian racism in the US); and on the other, instances of their forced enclosure, when, for example, the US Federal Army was stationed in Rock Springs, Wyoming for fourteen years, following the 1885 Chinese Massacre, in order to prevent Chinese miners employed by the Union Pacific from escaping white racial violence (Figure 23). As Tao Leigh Goffe has written about enslaved African, indentured Asian, and racialized peoples across empires, “in the historical ledger barely a trace of these subjects’ intimate, interior lives is recorded,”22 and thus we must utilize interdisciplinary, subversive strategies and draw upon our converging histories and intellectual traditions to see them.

Figure 23. Giving face to ancestor-cousins in 1890 Sanborn map of Rock Springs, Wyoming, Eastern Shoshone and Cheyenne lands. Animated image by author.

Back in Los Angeles, I worked with artist and bookmaker Taylor Zanke of Allowing Many Forms to produce an artist book, titled In Case of Fire 万一火灾,23 which could attempt to make visible what is missing from the archives while giving face to the people who endured horrific violence and yet were more than those experiences (Figure 24). I was guided by brilliant artists and scholars in sifting through archival photographs and my own photos to register narratives across time, following methodologies of Mitchell Squire’s portraiture and performance, Saidiya Hartman’s speculative histories,24 Katherine McKittrick’s critical geographies,25 the Chinese diaspora archeologies of Kelly N. Fong 方少芳, Laura W. Ng 伍穎華, Jocelyn Lee 李紫瑄, Veronica L. Peterson 孫美華, and Barbara L. Voss,26 and what Édouard Glissant termed le droit à l’opacité, or the right to opacity.27

Figure 24. Details from Bz Zhang, In Case of Fire 万一火灾, handmade artist book, created while artist-in-residence at Allowing Many Forms (Los Angeles, CA), 2022. Photographs by Allowing Many Forms. (click to view moving image)

I found that by directly situating original source materials, rather than translating each archival and contemporary photograph into architectural drawings and documents, I could register more than spaces across time: I could in fact register a Chinese-diasporic gaze (mine) to both spaces and other gazes (most often, white and cis and male). At most of these sites, I had a choice of whether to include violent images and texts, and whether certain translations ought not to be made, and whether other translations might 给面子 gěimiànzi instead, to properly see these lives lived in wholeness.

As well, hegemonic narratives of Chinese diaspora in the Americas continue to disregard (or are unable to comprehend) experiences that are not cis and male. As Fong et al. write, “historic censuses list few Chinese American women and children… but family histories and missionary records describe diverse households, including intergenerational households, heterosexual nuclear families, single parents, and single-gender households.”28 I follow writers Patricia Powell, in The Pagoda, and, more recently, C. Pam Zhang, in How Much of These Hills is Gold, in wondering aloud: if even one Chinese-diasporic person assigned female at birth was there, I want us to look for them.

IV.

I have passed countless hours in the last years with Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, most frequently peering at digital reproductions through computer screens and scanning page-by-page for oil wells, refineries, coal mines, and then work camps, rail stations, lumber yards, and then Chinese laundries, “shanties,” and the words “female boarding” designating places of sex work. The time moves slowly. The cautious excitement of finding precious traces turns sour with the repetition of the archive’s callous disinterest—the word “C H I N E S E” stretched across entire neighborhood blocks without further detail—and I remind myself often to sit up straighter.

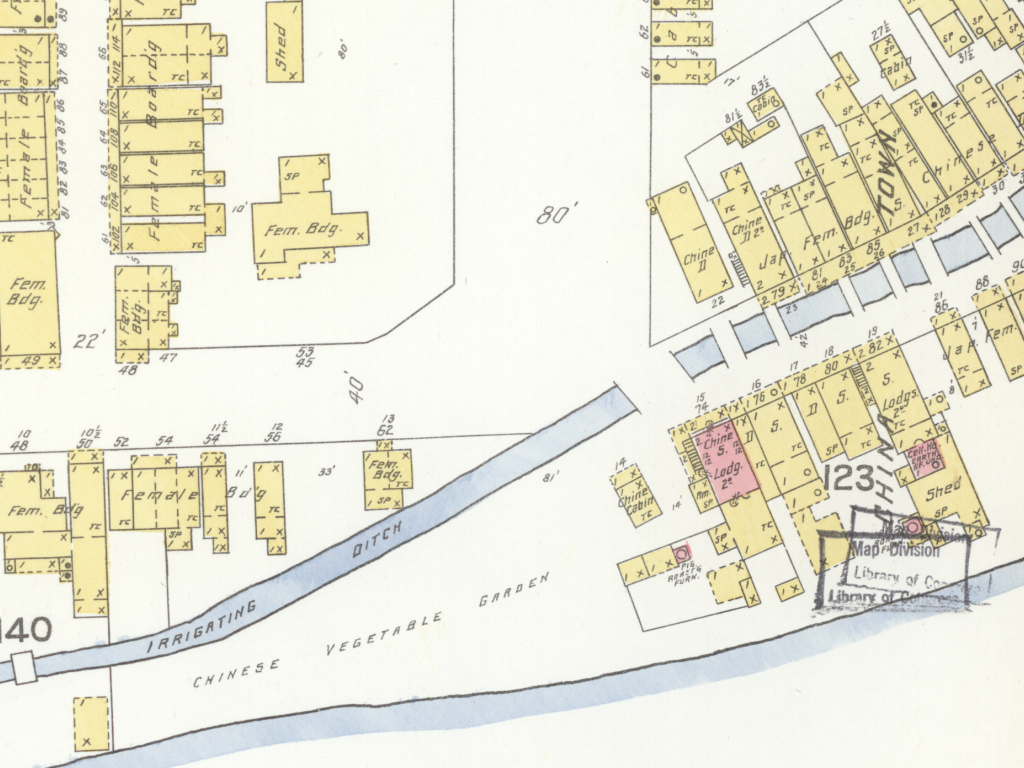

One day, I found a phrase I hadn’t yet seen before, scrawled on a 1904 Sanborn map of Reno, Nevada (the Chinatown had already been burned down once, in 1878, and would be burned down again four years later): “Chinese vegetable garden” (Figure 25).

Figure 25. Detail from Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, Reno, Nevada, 1904. Washoe and Northern Paiute lands. Library of Congress.

I unexpectedly cried upon reading those three words. I looked up from my desk involuntarily, as if to register whether anyone else (any other gaze) had seen it, too. I felt I needed to know who had written those words: was he—it was almost certainly “he”—struck by the garden’s size, its abundance, its smells, its sounds of Hakka, Toisan, Cantonese words and laughter? Was he disgusted; did he consider it a nuisance, a hazard to be documented; did he see the gardeners as human? Did he speak with them, the ways I wish I could? Elsewhere, scholars have documented cultural exchanges between Chinese and Shoshone, Paiute, Ute, and other Indigenous peoples, including the sharing of baahk choi (白菜, báicài, bok choy) and medicinal herbs,29 as well as the dependence of white Anglo-Americans on Chinese cooks and gardeners for survival in the West.30 I wasn’t necessarily uncovering something for the first or even the hundredth time, but I felt I had, in looking from this body, caught and held momentarily, across 100 years, the gaze of another body, looking at my ancestor-cousins and writing, by hand, those three words.

I don’t know that we can know the exact circumstances for how the words “Chinese vegetable garden” made it onto this fire insurance map, nor the dreams held by those who planted seeds within it. But on her way back from her own father’s funeral, my mother brought me seeds from our ancestral village in 安徽 Anhui and planted them for me in my backyard in 洛杉矶 Luòshānjī, Los Angeles. Without missing a beat, she harvested long stalks of bamboo, serving only as ornamental hedging in the moment before, and improvised a trellis for those vines to grow.

In an instant, she and I became bodies (ours), looking, from within an ocean of generations who have tended to choi yùhn (菜園 càiyuán, vegetable gardens)—diasporic translations of ourselves, our memories, and our communities as seeds passed through hands and earth and sea and sky, carried across unfurling scrolls of space and time.

Bz Zhang 张迪 (they/them) is an architect and artist based on unceded Tongva land (so-called Los Angeles) using disciplinary tools of architecture to imagine futures beyond settler colonialism, racial capitalism, and cisheteropatriarchy. They organize with Dark Matter U, the Design As Protest Collective, and the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust. Zhang is a 2022 Journal of Architectural Education Fellow, 2021 USC Citizen Architect Fellow, and a licensed architect in California. As a design professional, they have learned from and worked alongside contractors and fabricators in Philadelphia, architects and nonprofits in the San Francisco Bay Area, and artists and land trusts in Los Angeles. Their teaching practice has developed in collaboration with students and co-instructors at the University of Southern California, California College of the Arts, University of Michigan, University at Buffalo, University of California, Berkeley, Jefferson University, and Brown University. Zhang received a Master of Architecture from the University of California, Berkeley, and a Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Visual Arts from Brown University. In their free time, they look for birds and trash in the Los Angeles River.

Notes

- I trace my roots to 安徽 Anhui on my mother’s side and 山东 Shandong on my father’s side. I identify as Han in ethnicity and Chinese-diasporic as a political identity in kinship and solidarity across oceans and borders, in opposition and resistance to nation-states and empires everywhere. In this personal narrative, I primarily use simplified Chinese characters and pinyin transliteration to reflect my cultural context. However, in specific instances where referencing Chinese diasporic populations that speak in the Cantonese language family, I use the Yale transliteration of Cantonese and traditional Chinese characters first.

- Although my mother is a naturalized US citizen with a ten-year visa to China, all of our visas were suspended during China’s “zero-COVID” policies until March 15, 2023. Her father, my 外公, left us on December 29, 2022. We last saw him in person in the summer of 2019. Within the diasporic Sinosphere, I hardly know a single family who hasn’t been impacted in this way.

- Massimo Scolari, Oblique Drawing: A History of Anti-Perspective (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2015), 341.

- Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015).

- William Farish, “On Isometrical Perspective,” (Cambridge University Press, 1822).

- Cruz García and Nathalie Frankowski, “History Doesn’t Exist,” in A Manual of Anti-Racist Architecture Education (LOUDREADERS Publishers, 2023), 10.

- Sara Ahmed, “Queer Use,” Arcus Endowment of the College of Environmental Design, 16 Feb. 2018, University of California, Berkeley, https://grad.berkeley.edu/news/announcements/campus/sara-ahmed/

- Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use (Durham: Duke University Press: 2019), 41.

- Zoe Todd, “Fish, Kin and Hope: Tending to Water Violations in amiskwaciwâskahikan and Treaty Six Territory,” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry 43:1 (Spring 2017): 107

- Sandy Saeteurn, “11 years ago, the Chevron refinery exploded. It wasn’t a surprise,” Asian Pacific Environmental Network, August 6, 2023, https://apen4ej.medium.com/11-years-ago-the-chevron-refinery-exploded-it-wasnt-a-surprise-389c58f33927

- Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

- Neeraj Bhatia, “The Other California,” FOOTPRINT, The Architecture of Logistics. 23 (Autumn/Winter 2018).

- Angeline Robertson, “Linked Fates: How California’s Oil Imports Affect the Future of the Amazon Rainforest,” Stand.earth and Amazon Watch (2021), https://stand.earth/resources/linked-fates-how-californias-oil-imports-affect-the-future-of-the-amazon-rainforest/

- Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 98.

- Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press: 1984), 110–14.

- Tense Renderings: The Will and Won’t of Spatial Logics, curated by Simone Zapata and Fía Benitez, CalArts The Reef, Los Angeles, June 24–July 24, 2022.

- Anne Anlin Cheng, Ornamentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), 2.

- Saving Face, directed by Alice Wu (Destination Films, Forensic Films, GreeneStreet Films, 2004).

- Cheng, Ornamentalism, xi.

- Manu Karuka, Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers, and the Transcontinental Railroad (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019).

- bell hooks, “Black Vernacular: Architecture as Cultural Practice,” in Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: The New Press, 1995), 151.

- Tao Leigh Goffe, “Intimate Occupations: The Afterlife of the ‘Coolie,’” in Transforming Anthropology 22:1 (May 2014): 53.

- Whereas the English title, “In Case of Fire,” reflects the technical life and safety term in buildings and fire insurance maps, the Mandarin title, “万一火灾,” translates loosely and colloquially to “in case of a fire (disaster),” the way my mother might tell me to bring an umbrella in case it rains (“万一下雨!”).

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2019).

- Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006).

- Kelly N. Fong 方少芳, Laura W. Ng 伍穎華, Jocelyn Lee 李紫瑄, Veronica L. Peterson 孫美華, and Barbara L. Voss, “Race and Racism in Archeologies of Chinese American Communities,” Annual Review of Anthropology 51:233–50 (October 2022).

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 189.

- Fong 方少芳 et al., “Race and Racism”: 242.

- Hsinya Huang, “Tracking Memory: Encounters between Chinese Railroad Workers and Native Americans,” in The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad, eds. Gordan H. Chang and Shelley Fisher Fishkin (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019), 189.

- Sue Fawn Chung, “Beyond Railroad Work: Chinese Contributions to the Development of Winnemucca and Elko, Nevada,” in The Chinese and the Iron Road, eds. Chang and Fishkin, 325.