September 16, 2020-February 14, 2021

Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal

Francesco Garutti, curator; Johan Anrys, Joshua Bolchover, John Lin, and Freek Persyn, exhibition concept

The Things Around Us is an exhibition envisioned as a platform for rethinking the architect’s role in the dominant presence of the “planning logic of neoliberal urbanism.”1 In the exhibition’s online editorial, curator Francesco Garutti delineates the twenty-first-century architect as a visionary capable of radically reframing spaces. In spite of this, as stated by Garutti, most architects get reduced to service providers continually antagonized by restrictive neoliberal design ideologies. Rising against such lucrative market trends, The Things Around Us reconsiders urbanization by agitating architectural vocabularies, reframing analytical tools, and, building upon Bruno Latour’s philosophy, perturbing the notion of context. The exhibition focuses on two architectural offices, Rural Urban Framework (RUF) and 51N4E, which, according to Garutti, are already putting in practice new approaches to architectural contexts. Displayed in the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s main galleries, The Things Around Us is structured in five parts. Three large installation pieces organize the central galleries: a tall blue green-screen, a suspended polyester canopy, and a long blue table topped with fluorescent lights. Flanking the central axis, two symmetrical side rooms feature the World Trade Center skyscraper complex in the Northern Quarter of Brussels by 51N4E and the Ger Plug-in by the non-profit social enterprise GerHub and RUF.

The show opens on a somewhat contentious note. Designed by Berlin-based architects Something Fantastic, the tall blue screen dominates the foyer that introduces RUF’s and 51N4E’s four test sites: the ger district of Ulaanbaatar, a string of rural Chinese villages, Tirana’s city center, and Brussels. The blue screen is not a neutral setting. Green or blue backgrounds are used in video production and photography for an agent’s effective but superficial displacement into disparate environments. Chroma key tools often shed their green or blue cast on the subjects they put out of place. The exhibition uses it to suggest a procedure of inaugurating architectural contexts from scratch without problematizing the blue screen itself as a background.

Behind the blue screen, the suspended canopy transforms the following room into a mysterious storage gallery. The polyester NEWROPE Cabane canopy is devised to mimic the scenography of the Design in Dialogue Lab at the ETH in Zürich, led by Freek Persyn from 51N4E. At the ETH, the canopy frames safe spaces for dialogue; at the CCA, it frames a place for spectatorship. A juxtaposition of the canopy and the partially unrolled reels of Mongolian felt frames an exhibit of the film Untitled (The Things Around Us). Garutti and Irene Chin, curatorial coordinator at the CCA, conceived the film as a Latourian catalogue of agents and agencies organized in categories framed to represent species or classes of things. For example, video fragments of both urban and rural landscapes from Belgium, Mongolia, and China are grouped under the caption “The Nature.” In this manner, the film showcases concepts, objects, fabrics, sounds, and animals that affected RUF’s and 51N4E’s approach to design and projects. The video assembly presents an expanded ecology of RUF’s and 51N4E’s architectural practices intended to de-center the architect’s role by drawing attention “away from design or buildings as such,” as specified by the wall text in the gallery.

However, it remains unclear how showcasing a herd of sheep (that actually appears to be mostly goats) as a metonym for Mongolian nomadic culture draws attention away from the architects located behind the lens. The traces of the things in the film are ambiguous. For instance, it is uncertain how “The Sheep” influenced RUF’s projects in Ulaanbaatar’s outskirts or how arbitrary trucks from a stock video shaped their work in rural China. According to Latour in Reassembling the Social (2007), curators have to ensure that the actors evoked are incontestably there as an action is being redistributed. Put differently, a Latourian reading should enable us to trace associations between heterogeneous elements while slowing down at each traced step—making sure that the sheep are sheep: in Latour’s words, that as we build these networks, we are “good relativists.” It is not made clear to the visitor that the sheep and cashmere goats are evoked for any reason other than to historically or teleologically extend a series of intermediaries ad infinitum, thus essentially undermining the meaning of the network of things as a mode of inquiry.

A selection of things that irrefutably shaped the architects’ work is displayed in the three back rooms. Evoking an architectural fantasy banquet frozen in time, the blue table puts on view a vivid collection of objects: a drone; some office-branded tape; RUF’s toolkit for adaptations of vernacular typologies in Tongguan, Weinan; models and molds; a reproduction of 51N4E’s pavement cast for the memorial to four protest victims in Tirana; Edi Rama’s announcement of the competition for Skanderbeg Square in 2008; and more. On one side of the rooms, the table artifacts are framed with a pandemonium of images of plans, records, meetings, and buildings, documenting the projects’ development. On the other side of the galleries, going back to Latour, the search for order and rigor materializes in five refined diagrams distilling 51N4E’s and RUF’s projects under five themes: scale, perspective, threshold, time, and position.

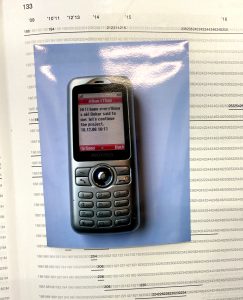

If the film exhibit lacked nuance and restraint in its portrayal of actors, restraint abounds in the blue-table galleries. If the show is supposed to be a laboratory for rethinking the architect’s place apropos global neoliberal ideologies, why are the most daunting geopolitical actors missing? How do we examine an object of interest from within a Dingpolitik, as described by Latour in Making Things Public (2005), with a set of significant agents and connections gone astray? For example, the curators show an image of a cell phone displaying a casual text message that announced the official resumption of the TID Tower project in Tirana. It showcases the turbulent Albanian political scene as a curiosity that excessively prolonged the work of the Belgian architects. Yet the controversies regarding 51N4E’s collaboration with Anri Sala, the tenders for Skanderbeg Square, and the office’s involvement with the Prime Minister’s private atelier-studio-villa in Surrel are unfortunately absent. Opening up these topics would have engaged the geopolitical and sociopolitical forces that pushed and pulled against the entire design ecosystem. Instead of profiting from controversies, the show’s designers and curators abstain from unfolding the political debates. Thus the ideologies that Garutti set out to tackle remain invisible, buried in some distant other ecology, i.e., censored.

This brings me to my last point. The Things Around Us urges us to negotiate ecologies, tools, models, documents, delays, and fabrics. The questions raised and the themes evoked speak to crucial issues that confront architecture worldwide, and for that, the exhibit is both thought-provoking and relevant. Yet the show often presupposes an “Us” that works to insulate the architects from all the things around them. We learn more about how architects make concepts from vertiginous experiences with the Other—the Orient, Eastern Europe, the nomad, postmodernist additions like the renegade modernist—than about reinventing context. If the CCA wants to de-center the architect, they should do it: unfollow Us and instead follow the Mongolian goats.

Endnotes:

Dijana O. Apostolski (M. Phil., 2014, M. Arch., 2016) is a doctoral candidate at the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture, McGill University. Her research critically re-examines conventional European architectural histories and their main protagonists. She is currently working on representing Michelangelo’s paper architectures at the intersection of architectural history, art history and conservation, and the histories of body and religion. The McGill Engineering International Doctoral Award, the Peter Guo-hua Fu Graduate Award, and the Schulich Graduate Fellowship support her research.

How to Cite This: Apostolski, Dijana O. Review of The Things Arounds Us: 51N4E and Rural Urban Framework, curated by Francesco Garutti, exhibition concept by Johan Anrys, Joshua Bolchover, John Lin, and Freek Persyn, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, September 16, 2020 – February 14, 2021, JAE Online, October 23, 2020, http://www.jaeonline.org/articles/review/things-around-us#/.