REVIEW

AUGUST 19, 2023–JANUARY 7, 2024

HEINZ ARCHITECTURAL CENTER, CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF ART, PITTSBURGH, PENNSYLVANIA

ALA TANNIR AND THEODOSSIS ISSAIAS, CURATORS

Tucked within the surprisingly earnest postmodern halls of the Heinz Architectural Center in the Carnegie Museum of Art, Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground offers a visceral portrait of extractivism. Cocurators Ala Tannir and Theodossis Issaias display a variety of media that engage mourning, loss, and action in times of climate and social transition. Anchoring seven new commissions alongside seven historical artworks from the Museum’s collection, the curators build the scaffold for an institutional critique without getting mired in the details.

Figure 1: Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground installation photo. Photo credit: Sean Eaton, Carnegie Museum of Art.

The historical artworks serve as the foil for the contemporary works, without offering a decisive dialectic between the “good” and the “bad.” In 1954, Fortune magazine and the Joy Manufacturing Company sponsored an exhibition that invited seven painters and illustrators—including the New Yorker illustrator Saul Steinberg—to produce the Continuous Miner series representing the Joy Manufacturing Company’s new caterpillar-like automated miner. Rather than offering simplistic corporate valorization, the series shows a complex, critical picture of automation, the environment of the mine, and of the human labor held within. The paintings by Antonio Frasconi and Rufino Tamayo—later removed from a retrospective by Fortune magazine—include human figures supporting the orange mining monster as it churns through the earth. Similarly complicated in attitude, Hedda Sterne’s The Continuous Miner (1954) situates the automated beast within a painted representation of a mine made of silver paint and broken glass that mimics the subterranean shine of anthracite. The series’ inclusion in Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground thus illustrates the difference between the possibility of critique within the historical corporate-funded art and in the community-centered methods employed by the contemporary works.

Figure 2: Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground installation photo. Photo credit: Sean Eaton, Carnegie Museum of Art.

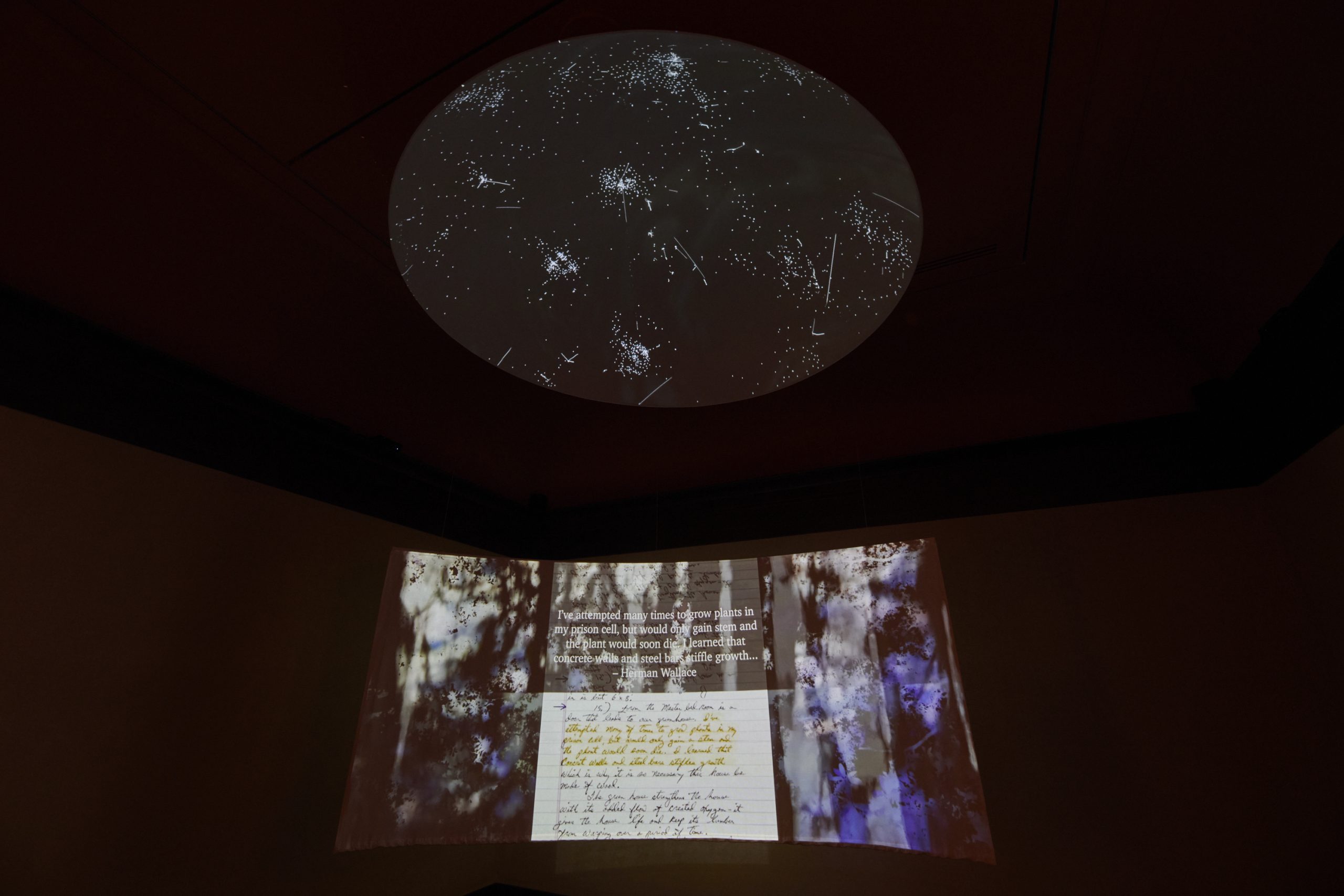

In the accompanying exhibition catalog, the curators contextualize the show within contemporary discourses of extraction and activism. The coupling of community action with a profound reckoning with the environmental and human loss caused by fossil fuel infrastructure remains a common thread throughout the exhibition. For example, in a conversation between urban theorist Keller Easterling and artist-activist Imani Jacqueline Brown in the exhibition catalog, Brown discussed how Black funeral processions in New Orleans support the living while honoring the dead by visiting community-owned businesses along the route. Brown’s video installation and poem The Holes in the Earth Mirror the Holes in Our Souls (and from Them We Can Grow Trees) (2023) illustrates the “layer cake” of subterranean oil, pipeline, human burial, nonhuman burial, and increasingly poisoned air that constitutes Louisiana’s Cancer Alley. It also marks a Black burial site—covered in trees that pull atmosphere, earth, and human ritual together—as a critical point of resistance to exploitative labor and environmental destruction where the dead can aid the living.

Figure 3: Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground installation photo. Photo credit: Sean Eaton, Carnegie Museum of Art.

Two rooms away, four rough-hewn wood masks silently watch set-camera footage of themselves appearing outside different sites of energy infrastructure from Pennsylvania to the Pacific Northwest. The piece We Refuse to Die (2023) from the collective Not An Alternative foregrounds mourning practices as a critical component in the fight against extractivism. The masks—in video and as audience—sit atop wood poles and condemn the steel and oil behemoths they watch. The collective juxtaposes video showing the ritualistic carving of these animal-head masks from wood scavenged from burnt forests with members of the communities directly affected by the outflow of the chosen energy sites. The distance of callous conceptual critique more typical of art produced in an isolated studio is erased as the collective embed themselves within communities most affected by the given factories, pipelines, and refineries to perform rituals highlighting human loss while the animal-head forms of the mask highlight the loss of our nonhuman relatives either directly by the forest fires that created the wood or by the pressures caused by extraction and changing climate.

Figure 4: Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground installation photo. Photo credit: Sean Eaton, Carnegie Museum of Art.

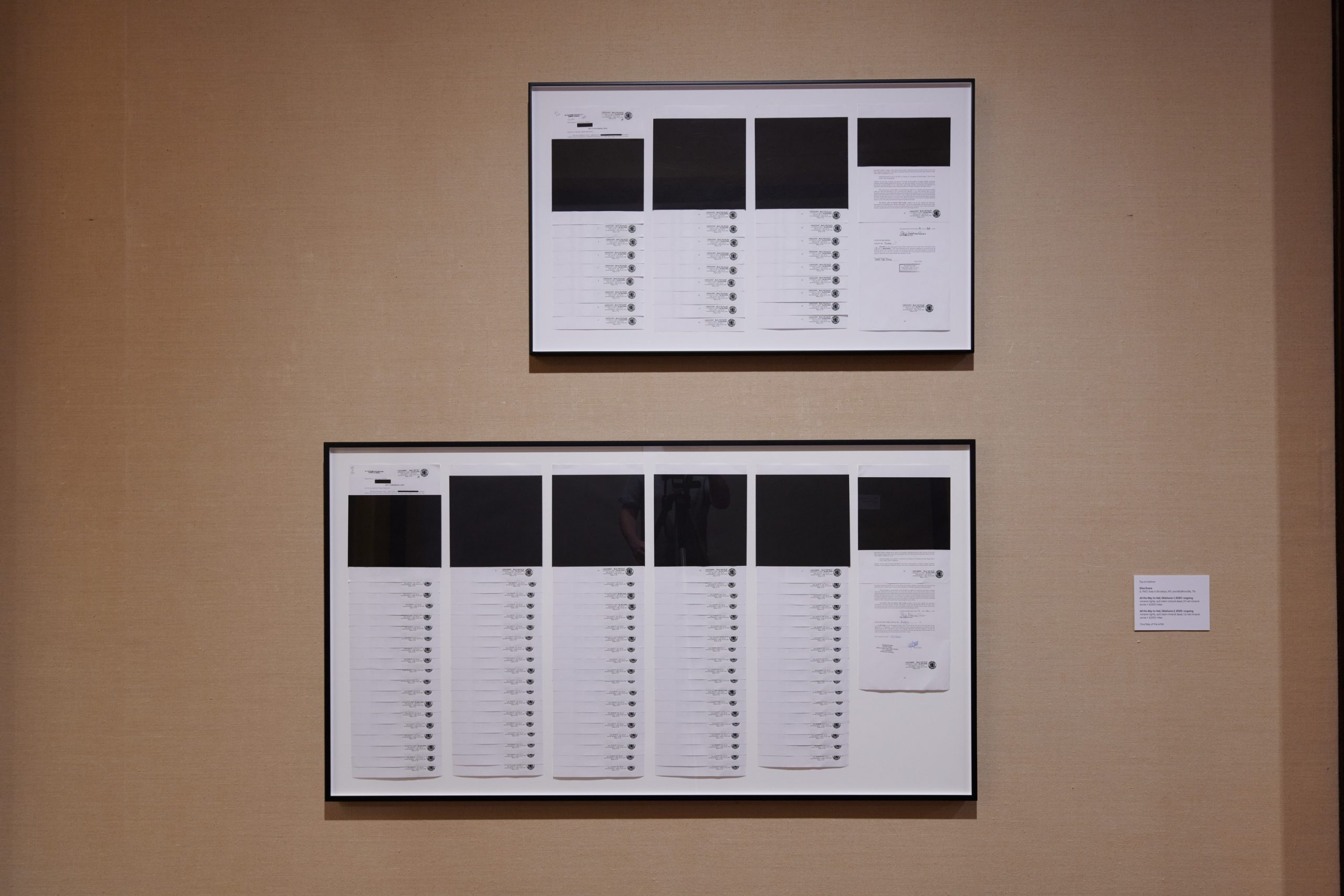

Taking another tack, Eliza Evans’s All the Way to Hell (2020 to present) sidesteps the loss of mass political action under neoliberal economics by infiltrating the system of byzantine property rights and accelerating its terms. A participatory project that buys mineral rights and disperses them amongst as many owners as possible, All the Way to Hell aims to produce an immaterial bureaucratic block between oil and gas companies and material extraction. Evans places contracts and deeds for protected lands in Oklahoma and Pennsylvania next to core samples extracted from the Permian Basin near Midland, Texas in order to shorten the distance between the transcendental framework of law and the material reality of place. By engaging Western extraction in its language of abstraction, Evans’s project deals with the pain of climate destruction by accepting the continued existence of private property rights in the foreseeable future and manipulating them for collective benefit.

Figure 5: Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground installation photo. Photo credit: Sean Eaton, Carnegie Museum of Art.

By shedding the positivism and positivity of mainstream climate discourses, Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground constructs a world of distributed localities that operate across scales and times. Pittsburgh’s eccentricities are well represented in Tony Buba’s Braddock protest documentary 40°24.2983’ N 79°58.251’ N (2023) and Walter Hood’s The Hill series (2023): two works that expand on the necessity of specificity in response to the neoliberal economic transition even across the same city. Both Cooking Sections’s Offsetted and Laia Celma and Pep Avilés’s Dystopian Carousel index external events across the state by bringing unconventional materials into the gallery: trees both natural and artificial for the former, and anthracite for the latter. Climate, extraction, and economies are demystified by the artists. Their focus on the localized phenomena of extraction and destruction allows the audience space to engage these fields as the paralysis caused by both the global climate crisis itself and stagist developmental theories loosens and allows for action. As Gökçe Günel writes in “A Spaceship in the Desert” in the exhibition catalog, historical transition is linear neither in time nor space. The show asks how we deal with our own feelings surrounding the local and global outcomes of climate collapse in the midst of these nonlinear transitions and encourages us to work through our own localized infrastructures in this time of monsters.

Unsettling Matter, Gaining Ground makes no attempt to use the museum to teach; instead it demands that the institution learn. The Carnegie name has direct ties to American energy infrastructure and it recalls a philanthropic mission originally laden with corporatocratic ideology; Carnegie’s libraries—given first to the communities of Carnegie steelworkers that did not often strike—would attempt to discipline the workers they claimed to educate. In the shadow of that name, the show realizes a new relationship between museum and polity. Knowledge is not collected and curated in order to emanate taste from the gallery outward—as the postmodern styling of the gallery would have aimed to enculturate the public that passed through it. Instead the curators and their artistic collaborators force the institution and the audience to move beyond the failing tools of abstraction and into the messy life of radical practice.

Andrew Economos Miller is a designer and educator who uses the trash pile as a tool for the deconstruction of architecture as an imperial labor form. They are interested in heterogeneous materiality and the intentional demolition and reconstruction of the built environment toward new social forms. They were the 2022–23 Schidlowski Emerging Faculty Fellow at Kent State University and opened their exhibition Refuse//Repose in Spring 2023. They are currently practicing in New York and adjunct faculty at the Lehigh University Department of Art, Architecture, and Design.