Erkin Özay

Routledge, 2020

Many hopes and promises of “fixing” today’s struggling cities center on the twenty-first-century public school as a potential panacea. In Urban Renewal and School Reform in Baltimore: Rethinking the 21st Century Public School, Erkin Özay uses the Henderson-Hopkins school campus in East Baltimore as a case study to analyze and unpack the promises of urban renewal. Henderson-Hopkins, which opened in 2014, was the first new public school in East Baltimore in over twenty years and a great deal depended on its success. Özay deftly explores the role of public schools in attempts to address decades of disinvestment and decline in Black neighborhoods while acknowledging the limits of what public schools can provide. Özay makes it clear that no one school, no matter how innovative, can address the trauma from decades of racial segregation and disinvestment. However, the book shows those in power attempting to use design to counter the effects of development with displacement as they try to rebuild better.

Özay shows that the material realities did not always reflect the lofty ideals. The author writes on page 5: “Led by high-minded ideals of city and school building, the case reveals the potencies and fault lines in our current thinking on the role of the public school as an instrument of urban redevelopment in distressed neighborhoods.” As the first city to legalize neighborhood segregation in 1910, Baltimore also, according to historian Emily Lieb, used public schools to initiate and sustain neighborhood segregation.1 Public school segregation drove neighborhood segregation and, therefore, reforming public education serves as a logical tactic to shift and refocus how we envision cities today.

Özay provides the history and broad context of the immense East Baltimore Development, Inc. (EBDI), an initiative founded in the first years of the twenty-first century. Nearly $2 billion has been invested in EBDI. It has served as a model of redevelopment through “eds and meds,” where institutions of higher education and hospitals act as anchors and catalysts for rebuilding cities. In recent scholarship, EBDI has also served as a representative case of development with displacement as the poor and Black Middle East neighborhood was largely demolished and transformed into Eager Park. EBDI led the extensive redevelopment efforts surrounding the Johns Hopkins Medical Campus and the creation of the Henderson-Hopkins school, itself a redevelopment project of massive scale.

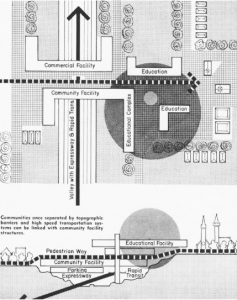

The book is comprehensive, interdisciplinary, meticulously organized, and readable. The first chapter goes over the history that led East Baltimore to a crisis and the narratives of community-focused development and education that offered potential solutions. In the next chapter, the author gives an excellent summary of the rise of the EBDI development and its many players. The third chapter addresses the emergence of the community school as a way to recalibrate this massive development project towards the community. Chapter 4, “A New Park and a New School,” delves deepest into the design and built environment that emerged from the lofty rhetoric and the attempt to be less top-down. This chapter includes numerous maps, renderings, and photographs. The final chapter locates the East Baltimore case study within the scope of similar initiatives in the comparable cities of Detroit and Milwaukee.

Özay locates the planning and construction of the Henderson-Hopkins campus and its innovative design within both the history of the redevelopment and contemporary debates. The book blends analysis of urban design, architecture, and education policy. It begins by exploring why this school matters for those debates. The push for a new public school in East Baltimore was something community organizers and developers could agree on as a potential public good. Community organizers like Lucille Gorham are central in understanding both resistance and the human costs of displacement. Baltimore’s Mayor when EBDI was founded, Martin O’Malley, leaders from Johns Hopkins University, and powerful non-profits involved in the development project all saw the extensive displacement of Black residents as a “bitter but necessary first step” (5).

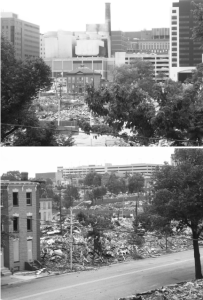

The design of the Henderson-Hopkins campus was intended to work with and reflect the feedback of the community; however, much of the community had been displaced and dispersed. EBDI hired consultants to try and track down those who were displaced from earlier stages of the redevelopment, without much success. The school’s design was an innovative and iterative process. The traditional classroom model was replaced by a more open and malleable group of common spaces with moveable “huts.” Flexible learning areas and smaller, more integrated classrooms and open spaces were implemented, but they demanded a great deal from educators and students. It becomes clear that it was far easier to tear things down than to rebuild them in East Baltimore.

Figure 3. Middle East after demolitions, August 2006. Image © Janne Corneil. [Urban Renewal, 77]

One strength of the book is that it develops characters, from the community organizers to the university presidents involved. Rather than voice a tirade against a redevelopment project that did not realize its social goals, Özay shows what had potential and what failed. The vision was not truly collaborative. A major flaw was in perspective—specifically the inability of developers to truly see Middle East and its residents when designing Edgar Park. Quoting Donte Hickman, an East Baltimore pastor, Özay writes: “the EBDI endeavor changed how East Baltimore communities perceived urban interventions, often raising the question, ‘Who are you building for?’” (120). This is a central question in the book and one that is still heard throughout Baltimore and cities like it today.

Özay’s case study of the Hopkins-Henderson campus provides insight to better envision the human potential already within the urban landscape. Still, at the conclusion of the book, the reader is left wondering why cities continue to focus on failed redevelopment plans that cannot see a community as an asset until it has been wiped from the landscape. Books like this one get us to reflect on the process of redevelopment, design, and the public good. Part of that ongoing and iterative process is for scholars and policy makers to learn to see what is already on the landscape. Such studies may provide us with a deeper understanding of urban redevelopment and design based on seeing one another’s humanity and thinking more critically about what we lose before we start tearing things down.

Notes:

Emily Lieb, “’Shove Those Black Clouds Away!’: Jim Crow Schools and Jim Crow Neighborhoods in Baltimore before Brown,” in Baltimore Revisited: Stories of Inequality and Resistance in a U.S. City, ed. P. Nicole King, Kate Drabinski, and Joshua Clark Davis (Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press, 2019), 24–36.

Nicole King, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of American Studies and director of the Orser Center for the Study of Place, Community, and Culture at UMBC. Her research focuses on issues of place, power, and economic development. She is an editor of the book Baltimore Revisited: Stories of Inequality and Resistance in a U.S. City (Rutgers University Press, 2019).

How to Cite This: King, Nicole. Review of Urban Renewal and School Reform in Baltimore: Rethinking the 21st Century Public School, by Erkin Özay, JAE Online, April 22, 2022.