Hiba Bou Akar

Stanford University Press

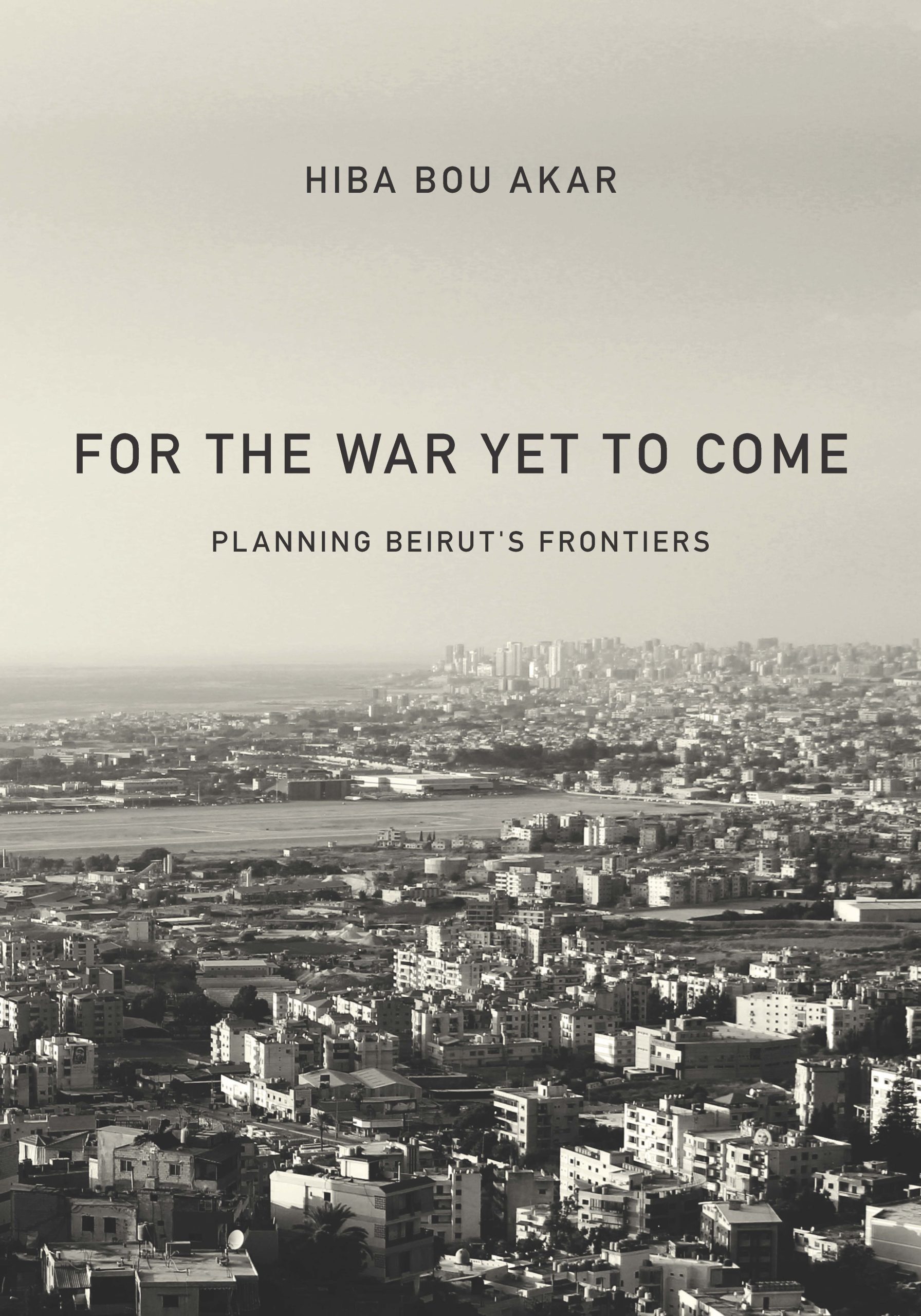

When I visited Beirut in 2013, the cosmopolitan milieu of the city was evident. Its vibrant business district, the corporate feel of the new housing and commercial development along the city’s seafront, the redevelopment of a reclaimed landfill as an opened green area, the beauty and historical nature of the American University of Beirut, and the French historical character of its architecture, all presented a complex and dynamic city. I was also impressed by the diversity of languages, religions, and cultural institutions in the city. Yet the bullet holes still present on buildings were a stark reminder of Lebanon’s civil war. I also had the opportunity to visit a Palestinian refugee camp on the outskirts of town and came away with a deeper understanding of the city’s political and social struggles. As an urban planner, my attention was drawn to the spatial “story” of the city, fascinated by both the physical and socio-cultural relations that shaped the city’s formation. A question that I pondered while visiting was how religion shaped and continues to shape the formation of the city. Hiba Bou Akar answers that problematic question in her excellent study of Beirut from its southern periphery.

For the War Yet to Come: Planning Beirut’s Frontiers, Hiba Bou Akar’s exceptional book, lays out the role urban planning has played in the city’s development. Bou Akar impressively weaves a complicated story of how Beirut’s sectarian conflicts dictated the city’s growth and, in turn, how that growth and development, what she terms “planning without development,” is used as a tool for supporting sectarian differences and power struggles to control the city. The city’s sectarian power struggles include the Druze, Shiite, Sunni, and Christian populations who influence planning and development to further their territorial claims.

Bou Akar makes an essential contribution to the urban studies and planning fields. She demonstrates the shadow side of planning—that is, how planning is used politically for sustaining and amplifying sectarian differences and violence. Bou Akar argues that in the planning literature, planning is framed as a pathway to progress, peace, order, and freedom.1 However, Bou Akar’s study shows that there is a shadow side of planning—to encourage conflict, emphasize difference, and create fear for the war to come. A central finding of her book is “that planning can be a tool of war as well as peace” (184).

The book focuses on planning as a tool of war. Bou Akar employs a planning logic that she terms “the war yet to come” to uncover the complicated urban planning relationships in Beirut’s sectarian frontiers. As she explains, “The war yet to come thus approaches war not as a temporal aberration in the flow of events, with a beginning and an end, but as a state of affairs expected to reoccur … the anticipation of future war has thus become a governing modality within Beirut’s peripheries” (7). Her astute framing helps us trace planning’s role within Beirut’s geographies of war during times of peace. She demonstrates how fear and the future threat of violence spur specific economic and physical development in neighborhoods on the outskirts of Beirut. Her analysis of Beirut’s planning political economy is fascinating and insightful, as the following quote demonstrates.

Planning for future conflict is also responsible for the ongoing creation of frontiers in Beirut. Structured by past wars and in anticipation of new ones, this new condition involves more than battlefield logics or paramilitary maneuvering. It involves the calculated construction, in times of peace, of a spatial order of sectarian and political difference. Thus, this book has additionally sought to reveal the important role played by religious-political organizations in shaping urban planning and zoning schemes, land and housing markets, and the provision of infrastructure. (177)

Bou Akar can develop such insight by engaging in what she terms an ethnography of spatial practice. She investigates how territories are shaped by practices and discourses of fear, conflict, and war (12). This methodological approach helps her conduct an ethnography of planning logic, its hidden political purpose, and on-the-ground outcomes. Her position as a planning academic, a practicing planner in Beirut with her family home in the city, means she is well situated to conduct the ethnography of spatial practice.

Bou Akar’s explanation of “planning without development,” the title of chapter 5 in the book, is filled with essential insights into how planning is used as a political tool for furthering sectarian violence. If you accept her definition of planning, her analysis falls nicely into place and supports her central argument. She views planning as a Western European colonial technical tool of spatial control and management of the future. In her words, “Planning … can be understood as a set of philosophies and practices related to the organization of space, which are guided by a set of temporal ideas regarding uncertainty, progress, and the future” (148). Based on this definition of planning, Bou Akar argues that when planning loses its ethical mandate for justice and equity, it becomes a spatial tool for the elite and those in power.

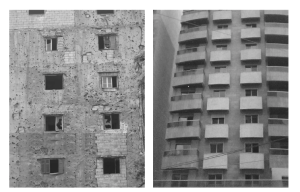

The Beirut case demonstrates the dark side of planning used for increasing violence and manipulating the populace through spatial and territorial control. Bou Akar’s compelling argument is that planning and architecture are tools that help create sectarian political order and spatial problems. Accurately, Bou Akar describes planning without development as:

localized planning through an allotment among religious-political organizations, which in turn reinforces or facilitates an ever-shifting division of urban space along sectarian lines. [Planning without development] has allowed militias and religious-political organizations to configure space in their own interests, not only through the “sticks” of militarization, violence, and forced migration but also through the “carrots” of housing development and social service provision. (177)

Through her grounded ethnography, Bou Akar demonstrates how the “carrots” of development services support sectarian difference and ultimately increase conflict. She also argues that planning produces contested—as opposed to harmonious—geographies, which leads to uneven geographies of segregation, poverty, environmental degradation, and violence (180). The key mechanism used by sectarian organizations to increase their power is creating a sense of fear for the future within Beirut’s population. Fear of terror, gang violence, and racial antagonisms produces urban growth and spatial management in Beirut’s peripheries.

The book ends with an encouraging note describing new movements that challenge sectarian-based political alliances and their doctrine of fear. Alternative groups such as Beirut My City have rallied to create planning interventions based on non-sectarian social principles. I would have liked to have seen more emphasis provided in her analysis regarding these alternative groups engaging in planning movements that bring new spatial and political imaginaries for a more equitable Beirut. But while that emphasis could have been stronger, the book is an excellent dive into Beirut’s planning politics and an essential contribution to urban studies and planning literature.

Endnotes:

Gerardo Francisco Sandoval is an associate professor of planning, public policy, and management at the University of Oregon. Dr. Sandoval’s research is situated within the intersections of neighborhood planning, immigration, and community change. He received his Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley.

How to Cite This: Sandoval, Gerardo Francisco. Review of For the War Yet to Come: Planning Beirut’s Frontiers, by Hiba Bou Akar, JAE Online, September 11, 2020.